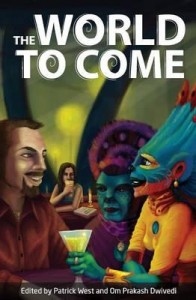

Our latest anthology, The World To Come, features short speculative fiction by nineteen writers from here and overseas. In this series of interviews we ask the authors about the story published in The World To Come, about their views on the speculative fiction genre, who and what influences their writing and for some inspirational tips.

1. Tell us about your story in The World To Come.

Awake is set in the early days of a future dystopia in which, for reasons unexplained, all human beings die if they fall asleep. Unusually for me, the story is told in the first person. Its narrator is a young man who, like everybody else, will do anything to stay awake. His mother has already fallen asleep, leaving only his father and a brother. The three of them have developed a routine to keep each other awake – a regular rollcall, physical jolts. Their house overlooks a large city that is slowly being destroyed as a result of its inhabitants’ inability to sleep and wake up again. Every night there are firework displays and rock concerts to delay the inevitable but there is little hope of a lasting solution.

The mood of the story is nostalgic and elegiac. I tried to build into it the sense that the narrator is an unreliable one because he is so tired, that he can’t remember, for example, if he’s already shared certain details with the reader or not. There is normally a political charge to my stories in the speculative fiction genre; Awake, however, is a relatively straightforward piece of storytelling. It may be that it works as a metaphor for the dangerousness of ignorance but I did not have that in mind while writing it.

2. In The World To Come ‘science fiction mixes with fantasy, with realism in all its sub-genres, with speculative fiction, with the almost unclassifiable’, according to its editors. What thoughts do you have on the current status of short fiction in your part of the world and the genre/s in which you write?

Except in rare instances, such as Chekhov or Carver, literary credibility has never been bestowed on the short story. It’s always been regarded as a secondary activity, something established writers do around ‘important’ things like novels and plays. This is still true, and magnified in the case of ‘genre’ fiction which has also seldom historically been taken very seriously. However, there are still plenty of avenues in Australia – established journals like Meanjin and Overland, new ventures aimed at a younger demographic like The Lifted Brow and Kill Your Darlings – for the publishing of short fiction. For better or worse, the genre has also expanded during my lifetime into new areas like flash fiction, and the digital space has created fresh opportunities.

As for speculative fiction, I don’t in all honesty know much about where the genre is at in Australia. As a rule, I find myself reading more non-fiction than fiction these days. More broadly, I worry that the speculative fiction genre has come to be choked by the dystopian – and I say that as someone whose story in this collection, and whose first full-length play, have dystopian settings! I’d like to see a return of the utopian imagination, genuinely speculative rather than scientific, to counter the unrelentingly dark dystopian narratives that seem to be everywhere at the moment.

3. Who, or what, inspires your writing?

There is no point being general about this question, so two recent and specific examples: the short stories of fellow Adelaidean Peter Goldsworthy, which have lessened my cultural cringing and shown me that it’s alright to be specific about place in fiction (even if that place happens to be ‘only’ Adelaide); David Eagleman’s Sum: Forty Tales from the Afterlives, lent to me by a friend, and an unexpected catalyst for one of my latest projects, a short story collection on the theme of utopia.

4. Tell us what you do if you haven’t written anything in a while and you want to get started writing again? Could you share your favourite writing exercise with our readers?

4. Tell us what you do if you haven’t written anything in a while and you want to get started writing again? Could you share your favourite writing exercise with our readers?

If you are in any way serious about writing, you should never let yourself get into this situation. You ought to write something every day, even if it’s not very much or you think you might ultimately discard it. Keep the chain well oiled, in other words, and you should never have any problem setting off. As for writing exercises – I don’t have much of a repertoire, but I’ve always liked playwright Mark Ravenhill’s rule which he calls ‘all change’: if you are stuck, just treading water, change something, anything – make a letter arrive, make one of the characters turn angry. It may not work when you come back to it the next day, but at least you will have gotten something down instead of just agonised uselessly.