- Jen Craig

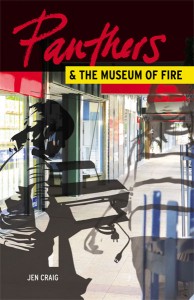

Jen Craig’s novella, Panthers and the Musuem of Fire was recently given a five star review and named Book of the Month by Australia’s premier book industry magazine, Bookseller + Publisher. In her review, Angie Andrewes described Jen’s book as ‘an experimental novella but surprisingly easy to read, and brilliant for the very ordinariness of its subject’. We are delighted to bring you the transcript of the extended interview between reviewer and bookseller, Angie Andrewes and Spineless Wonders author, Jen Craig.

AA: In Panthers and the Museum of Fire, the narrator is Jen Craig. In the past couple of years in particular we’ve seen a lot of writers, such as Karl Ove Knausgaard, Rachel Cusk and Sheila Heti, exploring new ways to work with memoir and fiction, blurring fiction with reality and forcing readers to question what is true. Would you say Panthers is more biographical or fictional? How much do you blur the lines?

JC: I can only say that on the one hand, the narrator is absolutely me – because I, like she, was named after, while in advance of, a multinational dieting company, and that there are a few people in my world who persist in calling me Jenny even though I will always, very firmly – unless it is one of my parents – correct them – but on the other hand, it’s pretty obvious that she is also not me at all. For one thing, I don’t live in Glebe. For another, I don’t work in radio – and I also happen not to be single or childless, which is not just a recent change, but has actually been true of me since sometime last century. And yet Glebe and, as it turns out, radio, is under my skin for various reasons, and there are so many aspects of myself in this book, and so much of my life is in there. All of it, in fact.

AA: It is clear in this novella that you are influenced by many different writers with different styles. You directly reference numerous works, and there seem to be quite a lot of comparisons between Joyce’s Ulysses and your latest work. Who or what work would you say had the most influence on you while you were composing Panthers and the Museum of Fire?

JC: It is interesting that you can see something in this work that could be compared to Joyce’s Ulysses. If this is so, it is completely unconscious. Of course, there is the walking through a city – I can see that – and the way the main action or event in the book occurs in a single day – a single morning, even (and before work!). But apart from that: my piece is one, undivided work – a single throw, if you like, and is actually much closer to Proust, despite its brevity. But having said that, I can see that the simple fact that my narrator is a woman, and that she is also rather breathlessly pressed in her narration, could have something of Molly Bloom’s monologue about it – a kind of Molly Bloom taking over the male patterning of things but not one to play into the fantasies that they might have of her, nor even what women often have about themselves, as sexual beings, as women. I think Orhan Pamuk’s short novel, The New Life, was an important influence on this novella. Although I have read it twice, I haven’t read it for some years – and all that remains of it in my head, apart from some images of people hurrying along the streets carrying grey plastic bags, and the extraordinary glare and speed of night bus journeys, is something of its urgency and its focus – its sheer determination. Another important influence has been Thomas Bernhard, who was the first to show me that so much didn’t need to be written at all, that you could cut to the quick – which for me, as for him, I think, are the driving nature of thoughts and the way they play out. I grew up in a household that was presided over by a very dramatic, hyperbolic and vividly expressive if usually contradictory monologist and it took me the work of Thomas Bernhard – first Christina Stead’s, but later Thomas Bernhard’s, to make me aware, very slowly, of what I could do with this dominating part of my experience in terms of form.

AA: Was there ever any manuscript in reality, or was this merely a device you used to drive the narrative?

JC: My first answer would be no – since this is a work of fiction – but in the reality of this fiction, there is indeed a manuscript, and this manuscript refers directly to my own sense of what actually happened in the middle of writing my first book. I had written pages and pages of it – it was already a whole world, but a world that only I was interested in. It wasn’t working (this world still exists, incidentally, and in a sense, exists behind that novel, even though it’s not visible at all). But then one day I read Thomas Bernhard’s very odd, relatively early work Gargoyles (in German it is called Verstörung, which actually means disturbance, if you put it into Google Translate, and don’t let it preselect the word as Icelandic). I had read a bit of his work before then – I think it was his trilogy of novellas, Amras, Playing Watten and Walking – although they hadn’t really done that much for me, and so I don’t know why I went back to him. But I did. And I think it was while reading Gargoyles – in fact, while it was gradually dawning on me that the book had been split in half quite monstrously by mad Prince Saurau’s monologue – that the first half of the book would be entirely unequal to containing the strange, paranoid perambulations of the Prince’s mind – that the first half of the book wouldn’t be able to contain its second half, and I didn’t care – that I realised something very important about my own experience of growing up, as I have already said, under the timid but striding shadow of probably the most dedicated, outrageous monologist that I have ever met – and that was when I realised that the earlier version of my first novel needed just the smallest metal hook that could be inserted about halfway into the thing to pull what was inside it onto the surface, and it was as if I had pulled the novel inside out. It was one of those aha moments – those breakthrough moments. That breakthrough actually existed then, and in that sense the manuscript definitely existed in the reality of my own biographical life. I have had one of those reading-writing experiences. That is entirely true.

AA: You write with a compelling sense of immediacy about Sydney and the suburbs of Glebe and Surry Hills, and the title of the novel is taken from a Sydney road sign. How important to you is instilling a sense of place in your work like this? Do you think it matters if your reader doesn’t know Sydney well?

JC: I do think place is important. It always makes a huge difference where I am and where I walk, which is probably why I am such a creature of habit. Perhaps, too, that’s why I’ve been living in the same crumbling sandstock brick terrace for close on 23 years. Having said that, though, I don’t think it is necessary for the reader to know Sydney to understand what is going on in the book, because place, in this novella, is filtered, almost entirely, through the narrator’s head – it is the narrator’s version of Sydney, and many readers will probably disagree with her version. Many will not even recognise it. The sign that gives the book its name, of course, will have a special resonance for people who live in western Sydney or the Blue Mountains. The original sign, as you learn in the novella, is no longer there – perhaps the local councillors were embarrassed or had got complaints that the tourist sign was referring to a rather well presented rugby league club, which might be the biggest employer of people in the area, but not exactly Michelangelo’s David. Yet the sign, as I describe it, was once there, and those who are familiar with it will have their own associations. One important aspect of Sydney that I probably take for granted in this novella – but which is built into it, I hope, nevertheless – is its incredible porousness – that is, its openness to the wind, the rain, the humidity, the persistent rub and grind and murmurs and music of street noise or neighbours, through our windows that never quite seal out the weather and our doors that have trouble even keeping out the leaves. Unless you live in an air-conditioned apartment, people in Sydney are never unaware of what is going on outside and we take it for granted that we need to adjust to it – to all the minutiae of the city’s sounds and temperatures. I know this because when you meet people who have come here from other parts of the world – Europe, Asia and even Africa – they usually complain about the weather – particularly the cold, even though it is never really cold here. It never snows. But when it’s cold in Sydney, the weather seeps under the doors and through the badly fitting windows, and most of us have some kind of pathetic heater that we put on sometimes or we generally just pile on more and more clothing. My father said that when he was in London in the nineteen fifties, he could always tell the Australians from the Brits because they coped better with the cold. The other aspect of Sydney that I don’t write about at all, but which hangs over the whole thing like some huge banner that has been unfurled overhead, is the wide, changing, impersonal sky and, particularly, its southerly changes. Christina Stead writes about this so vividly in her Seven Poor Men of Sydney. There is also the grotty side of Sydney – and this is a side of it that I love – the shabby student households, the shuttered down shops, the dog shit in the lanes, the bougainvilleas that grow so much more monstrous than were ever envisaged, and the scurvy weed that always takes over my best attempts at gardening. Delia Falconer writes about this kind of thing in her biography of the city, Sydney. Her Sydney is immediately recognisable to me.

AA: What was the last book you read and loved?

JC: This is a hard question to answer. I’ve just finished David Malouf’s book of essays, The Writing Life, which was an absolute pleasure. He has such a nuanced sensitivity to everything he reads – everything, I would say, except the early work of Christina Stead, which feels, to me, oddly removed. Even so, I could go on and on reading his essays. Right now I am reading Luke Carman’s An Elegant Young Man and absolutely loving it. I’d heard him reading sections of the book at various times in the last year or so, since he’s a fellow post grad where I am studying, and I was entranced. I particularly love those shifts he makes in his stories, where he turns what he says a half centimetre around very suddenly, only to turn it around again another bit more. I expected his punctuation to be much more eccentric than it is, though. It’s admirably clear. I am always trying (in vain!) to stop myself from putting em dashes everywhere. Some might say I could just use full stops and commas instead, but I know I need the sentence to continue past the interruptions, and in a certain rhythm – so that there still is half a breath or at least a quarter of a breath left in it from the earlier bit.

Ask for Panthers and the Museum of Fire at your local bookshop or purchase a copy from our online shop, here.

You can find more discussion of Panthers and the Museum of Fire on the Spineless Wonders Bookclub on Facebook where author Jen Craig was joined by editors Ali Jane Smith, Linda Godfrey and reviewer Angie Andrewes and other readers.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/spinelesswondersbookclub/