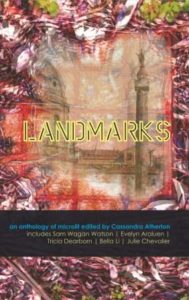

This week we talk with the 2016 regional joanne burns award winner, Dael Allison. Her recent work ‘Breakwall’ appears in Landmarks – the latest anthology curated by Spineless Wonders. During this interview we discover Dael’s favourite Australian landscape, who inspires her writing and what inspired her mirco-lit, ‘Breakwall.’

This week we talk with the 2016 regional joanne burns award winner, Dael Allison. Her recent work ‘Breakwall’ appears in Landmarks – the latest anthology curated by Spineless Wonders. During this interview we discover Dael’s favourite Australian landscape, who inspires her writing and what inspired her mirco-lit, ‘Breakwall.’

Tell us about a landmark that is significant to you

I am a fan of rocks. Rocks emerging or lying around, teetering in the face of gravity, hoisted and moved, sculpted by wind, water, hands. Any headland appeals. I am no intrepid scaler of verticals but a walk above a cliff face, or below it, is a fascination. Reading the stories the rocks compose, conglomerates of matter and existence trapped by molten capture or pressure. Whibayganba – Nobbys headland – is arguably the most recognised of Newcastle’s landmarks, so it feels clichéd to nominate it here. But there are many facets to Nobbys, from dreamtime stories of the great kangaroo beneath, which sometimes causes the earth to shake, to the role the landmark plays now as lighthouse warding ships away from undersea perils, as a place that draws people out, for fitness of body and mind, solace, fishing, romance and furtive exchanges. Whenever I walk along that breakwall the giant rocks intrigue me, their different geologies, densities, patterns, the way light, rain and spray fall across altering planes, their sheer size. Inevitably I speculate on how they were quarried and transported, back in the early 1800s, by convicts with little self-protection and few tools. Because back then Nobbys was not a headland. It was Coal Island, so named by the early white administration. Convict artist Joseph Lycett painted numerous views of the Coal River settlement which was to soon become Newcastle. One beautiful picture is of evening, with Aboriginal men performing a ceremonial dance in the foreground. In the distance the island is a shark-tooth shape jutting from the sea, a solitary entity guarding the mouth of the Hunter river. Tethered to the land, with its height reduced by half, the Nobbys we know today says much about human values.

What inspired you to write ‘Breakwall’?

Plaques and graffiti along the rocks of Nobbys’ breakwall. The way the elements in wild places, like those dark waves crashing in, exert a hypnotic lure. The impulse to abandon everything known. Shipwrecks, lost lives, simple humanity.

How do you find the experience of writing to a theme?

Having never completely left behind the primary school thrill of the teacher writing a composition topic on the blackboard, I love writing to a theme. Someone else’s thought process morphs into a mental scattergram of possibilities. So many possible paths to explore.

Describe your writing space

I move around a lot, but wherever I am I need a room with a view. Writing this, I’m revisiting Savai’i, Samoa’s largest island, where I have spent most of the last two months. On a small table with a red and white traditional-pattern cloth, I have a couple of pens, my laptop, and Google for research in lieu of books. Beyond lush brilliantly coloured foliage, the sea is turquoise or green or indigo or grey. A long way out, white water is constantly breaking on the edge of the reef. I can hear it, as well as whatever is happening in the village around me. The wet season might be tailing off but clouds still build rapidly to tower in the sky. In a closer perspective bulbuls, swiflets and the occasional kingfisher keep the air busy, while rails stalk the grass like elegant chickens and iridescent lizards scurry between the blades. This is all I need, a space for intense concentration, for unknotting the tangle of thought-lines, and somewhere to look out on that is both restful and energising. I know writers who prefer to face a wall to avoid distraction, but for me so much of writing is dreaming, and so much of dreaming involves staring out at leaves or sky or birds. Which no doubt explains why writing is generally a slow process for me.

Tell us about a writer or work that has inspired you as a writer

Only one?

When I first read Michael Ondaatje his writing was a revelation: his insight, vision, the way he crafted words, suspending my disbelief, making me think through connections. Everything so fresh. His first, award-winning novel, Coming through Slaughter, traced the mental decline of early jazz great Buddy Bolden, tangibly evoking the syncopated rhythms of New Orleans’ rag-time. Ondaatje’s characterisation and sense of place are superb in In the Skin of the Lion and its semi-sequel The English Patient – later an exquisite film directed by Anthony Minghella. His novel, Anil’s Ghost, and memoir, Running in the Family, created a long-time wish to travel to Sri Lanka, even more so now that my daughter recently sent beautiful, intriguing images from her time there. Ondaatje’s poetry, too, is sensual and deeply human, often quirky and left-field. The Collected Works of Billy the Kid: Left-Handed Poems and The Cinnamon Peeler remain two favourite volumes. I often revisit the title poem of the latter in which Ondaatje writes about love but also about writing, and the need in both for full immersion, to succumb completely to the art. For:

what good is it

to be …

left with no trace

as if not spoken to in the act of love

as if wounded without the pleasure of a scar.

Dael Allison writes poetry, essays and fiction and has received numerous literary awards. Poems from her book, Fairweather’s Raft, featured in soundscape on ABC Poetica. She is a PhD student in Creative Writing at University Of Newcastle.

Feature image via Pexels.com