As a fledgling writer Danielle Wood encountered Carmel Bird in the pages of Bird’s how-to book, Not Now Jack – I’m Writing a Novel, and immediately took her advice to heart. In this article, reprinted with permission from the Hobart Mercury, Danielle takes a close look at the extraordinary literary life of Carmel Bird and her long relationship with Tasmania.

As a fledgling writer Danielle Wood encountered Carmel Bird in the pages of Bird’s how-to book, Not Now Jack – I’m Writing a Novel, and immediately took her advice to heart. In this article, reprinted with permission from the Hobart Mercury, Danielle takes a close look at the extraordinary literary life of Carmel Bird and her long relationship with Tasmania.

Carmel Bird will appear in two sessions of the forthcoming Tasmanian Writers and Readers Festival in Hobart:

‘Our Heart is Her Heart’, in conversation with Danielle Wood, 2.30-3.30pm, Saturday, September 12, Hadleys Orient Hotel. Tickets, $15/$10, available from www.taswriters.org

‘Short, Sharp Shreds’, a short story celebration with Adam Ouston and Robbie Arnott, 3.45-4.45pm, Sunday, September 13, Hadleys Orient Hotel. Tickets, $20/$15, available from taswriters.org

In the world of one of Carmel Bird’s best-loved and most anthologised short stories, ‘The Woodpecker Toy Fact’, a ‘toy fact’ is a particular kind of truth – the truth according to the writer of fiction.

A toy fact can be absolutely true, or not quite. And even if it is a very long way from being true, then it will be so seductive that it ought to be. For Bird, such facts are the gorgeous, vivid scraps of stuff out of which stories are made.

Here is a toy fact: Carmel Bird and the cabbage white butterfly both arrived in Tasmania in the year 1940. Carmel sprang from her parents – her mother a creative soul and her father a Launceston optician with the magnificent name Will Power. As for the cabbage white: it came from Europe, via mainland Australia, and few gardeners relish the sight of the species’ slender green caterpillars on their brassicas.

Here is another fact, one that seems to chime quite nicely with caterpillars, butterflies and the transformative process that joins and separates them: Carmel Bird was born Janice Maureen Power, and Janice she remained while growing up in Launceston and studying to be a teacher of English and French. She took her birth name with her when she left Tasmania in 1963, but if getting married and then divorced taught her anything, it was that surnames could be acquired and abandoned with relative ease. And if this were true of surnames, then why not of first names, too?

‘I liked the music of Carmel. I did not especially like the music of Janice,’ Bird said.

As Carmel Bird, she has turned her mischievous, witty, dark, light, fierce attention on just about everything. She has written and edited more than 30 books, been thrice short-listed for the Miles Franklin Award (with The White Garden, Red Shoes, and Cape Grimm), and inspired countless other writers through her how-to manuals (including Dear Writer and Not Now Jack – I’m Writing a Novel).

Although she moved away from Tasmania in the early 1960s – and now

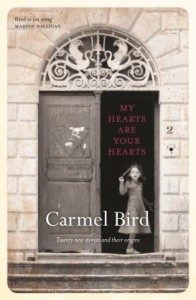

lives in Castlemaine in country Victoria – she has never really, truly left her birthplace behind. The two new books she has released this year, Fair Game: a Tasmanian Memoir and the short fiction collection My Hearts are Your Hearts contain plenty of evidence of how deeply the island’s trademark triangle is imprinted on Bird’s imagination.

‘I was born in Tasmania early in World War 2. In our bomb shelter there were maps – very pretty – of the world, and there was weeny little Tasmania, way away from where the war was. And there was also a huge map of Tasmania. I really loved the shape. I imagine that could be where my personal obsession with the place began,’ Bird said.

‘Because it was left off many maps, and was treated as a joke, and because the perspective my family and associates had of the world was focused far away (the war), it came to be that I perceived Tasmania as unreal. And I thought it was thrilling that I, being marvellously real myself, was roaming around in this non-existent place.’

When she ‘flew the island’, she took Tasmania and all its fairy-tale associations with her, hidden in a ‘fabulous, fictional capsule’ in her memory. And there, it has continued to echo.

Since she was fifteen years old, and possibly even earlier, Bird has been squirrelling away references to Tasmania from the obscure corners of world literature and popular culture.

Underlined in Bird’s 1950’s edition of Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts are the lines: ‘She had been born, but it was only gossip said so, in Tasmania: her grandfather had been exported for some hanky-panky mid-Victorian scandal’. In his autobiography, Hans Christian Andersen describes how a Lady Blessington keeps ‘a Tasmanian blackbird’ on her balcony. Small matter, Bird says, that there’s no such thing as a ‘Tasmanian blackbird’. The important thing, to Andersen, was that the warbling creature came from an unknown and exotic corner of the globe.

Charles Dickens, Somerset Maugham, Vladimir Nabokov, Agatha Christie and Noel Coward (‘I once had an aunt who went to Tasmania’) are also represented in Bird’s Tasmaniana snippet collection.

‘Tasmania [is] a name, a location, that pops up in literature when a writer seeks a far off, inconsequential, mythical or gruesome place to insert into the prose,’ Bird writes in Fair Game, her own most recent literary return to the island, and a story that began – like Bird herself – in association with butterflies.

A watercolour image of butterflies arrived some years ago in Bird’s mailbox, on a postcard. These butterflies have now taken up residence on the cover of Fair Game, a slender volume that has been exquisitely produced by boutique publisher Finlay Lloyd as part of its ‘Smalls’ series.

The image is from a cartoon lithograph titled ‘E-migration or a flight of fair game, 1832’, by English artist Alfred Ducote. A close look reveals that the butterflies are in fact women: their wings large, their feet tiny, their elaborate Georgian hair-dos adorned with tiny crowns.

But what Ducote is satirising – and what Bird has written about in her memoir – is far from a beautiful scene. In 1832, 200 young women were sent from England to Van Diemen’s Land aboard the ship Princess Royal – the first large group of non-convict women to make the journey – to become wives and servants in a colonial society suffering from a desperate gender imbalance.

In Ducote’s image, the butterfly women are being swept off the English cliffs by women with brooms. What awaits them in Van Diemen’s Land are men with butterfly nets, their speech bubbles exclaiming: ‘I spies mine’, or ‘I spies a prime ’un’. But these details are small and difficult to see.

‘It takes a very close look and a magnifying glass to release the narrative of the journey they are making from a hostile England to a rapacious Van Diemen’s Land,’ Bird writes. ‘It is not a joyful picture; it is a depiction of a chapter in a tragedy.’

Fair Game is a deceptive book, full of tangential musings, personal recollections and gossipy Tasmanian detours (‘I went to school with…’, ‘I once briefly dated…’), but by the last page, the final layer of has been removed and the reader has been brought face-to-face with the truth of what happened to many of those young women who crossed the world, poor and desperate, only to discover that they were absolutely ‘fair game’.

Bird has dedicated the memoir to her father, and also to Lucy Halligan, daughter of Bird’s close friend, the writer Marion Halligan. Before Lucy died in 2004 of complications from a life-long heart complaint, she was in the habit of sending postcards; it was she who sent the butterfly women to Bird, with a characteristically lively note on the reverse.

It’s hard not to hear the beats of Lucy’s ‘faulty heart’ echoing through Bird’s other new release, the short fiction collection Your Hearts are My Hearts. The hearts that Bird excavates in these stories might be anything from chocolate hearts wrapped in scarlet foil and displayed in a bowl, to transplanted body-part hearts, to the island of Tasmania itself, whose shape, in Bird’s ‘heart of heart…resembles that of a love heart’.

A private girls’ college in Deloraine, an artist’s home in the Huon Valley, and a second-hand imaginary version of Queenstown are among the Tasmanian locations that have made their way into the stories.

‘I didn’t have a rigid scheme for the collection, but the motif of the heart weaves and flickers through the narratives, and the stories do quietly sing to each other,’ Bird says.

Whether she is writing short stories or novels, it is all part of the same endless piece of string for Bird.

‘The first short story I ever read was “The Fly” by Katherine Mansfield. This was in Year Eleven and “The Fly” was a revelation to me. I have been a student and a practitioner of the form ever since. I will hear something, or observe something, and – ping! – something goes off in my mind, and a whole lot of details and recollections and voices gather, and I start to write a story,’ Bird said.

‘I also love reading and writing novels. I work on a novel and I write short stories at the same time, because I can’t help myself. My whole attitude to life, I suppose, is that of a writer of fiction, and I am, as it were, on the job all the time.’

I first met Carmel Bird in the pages of ‘The Woodpecker Toy Fact’, which hooked me with its opening description of women ‘magging’ over a paling fence, passing between themselves ‘hot scones wrapped in tea-towels, cups of sugar, bowls of stewed plums and a continuous ribbon of talk’.

But our second meeting – on paper, still – was a profound one for me. I had just given up my job in Hobart and was driving across the Nullabor Plain towards Perth and an uncertain plan to start writing fiction. It was January and my car had no airconditioner and by the time I reached Kalgoorlie, I was so hot that I didn’t care where I spent the daylight hours so long as it was indoors, and cool.

I found the library. I found Bird’s Not Now Jack – I’m Writing a Novel, and since then I have had total faith in the truism ‘when the student is ready, the teacher will appear’. Bird taught me, through the pages of that book, about the concept of suspending observations from life in the ‘marvellous clear jelly’ of fiction (and included a recipe for Japonica Jelly as well). She told me, firmly, that ‘real writers don’t have mothers’, which meant that I could not expect anyone to hold my hand or mop my fevered brow; I must just get on with it, alone. She urged me to give up housework. Her advice – on writing, and on the writing life – was and is golden to me.

While interviewing her for this article, I asked – somewhat nervously – about the how-to books, including my beloved Not Now Jack. They weren’t, were they, just something she did – the way writers sometimes must – to pay the rent?

‘No!’ she exclaimed, to my great relief. ‘No, they were much more than that. I loved writing them.’

Bird was first asked to teach a creative writing course in the early 1980s, a time when the concept of teaching creative writing was very new in Australian tertiary institutions. Soon she was also assessing manuscripts for the Victorian Ministry for the Arts. This process was anonymous and Bird was given the moniker ‘Number Eight’, with which she signed her reports.

Much of the advice in Bird’s how-to books came directly from the reports that ‘Number Eight’ wrote for real life writing hopefuls. The advice is enduring, and when Dear Writer was recently re-released (as an e-book and in paperback), the only details Bird really needed to change were to do with the march of technology in the publishing industry.

Bird has never been afraid of embracing technology, either within the worlds of her fiction, or in the way her work is presented to the world. She was the first Australian writer to have a website (her current site hosts a link to the original, ‘vintage’, model) and her book Red Shoes was issued with a CD-ROM appendix, at a time when such a thing was cutting edge technology.

‘I think communication, medical and space technology are all wonderful, but it’s also clear that technical progress is double-edged,’ Bird said.

‘Since at least World War 2 it has been more or less clear that the world is probably on a dizzy trip to disaster…the extinction of species, loss of crops, starvation, millions of refugees, the rise of sea levels, wild weather events. Bits of this get into my fiction, of course.’

Having just read Fair Game and My Hearts are Your Hearts, my mind is jostling with the many, many ‘bits’ – beautiful and terrible – that make their way into Bird’s fiction. There’s a $6000 raincoat from Paris, a monkey on the loose at a garden party, a retinue of faded Beatrix Potter figurines on a child’s grave, the broken insect that is the body a 15-year-old girl on the deck of the Princess Royal. And there’s Bird’s father Will Power standing in a Launceston garden on the day of an eclipse, comforting his little blonde daughter, who has just smashed a precious piece of green glass.

Look, Bird always seems to be saying to her readers. Look.