In this extended interview, Cassandra Atherton, microlit anthology series editor and regular judge of The joanne burns Microlit Award shares her insights into the history as well as the current state of play of the unique literary form, microliterature. She also talks about microlit videos, Japanese culture, micro-cocktails and her obsession with all things tiny. Cassandra is editor of Time an anthology of microlit and she will facilitate a panel on microlit at the Newcastle Writers Festival. Want to know more about writing microlit? Check out these Q&As with some of our authors.

- How did your interest in microliterature first come about and what attracts you most about the form?

I was nineteen when I started writing microliterature. It was mostly prose poetry and some flash fiction. I didn’t really know what I was writing back then – I just had these intense bursts of writing that seemed to work best in small paragraphs or fragments. At that stage I hadn’t come across Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen or the writing of Americans such as Russell Edson and Charles Simic, I hadn’t even read the ubiquitous six-word story attributed to Hemingway: ‘For sale: baby shoes, never worn.’

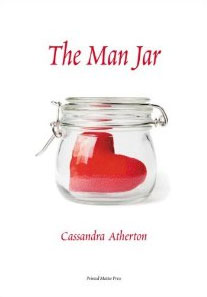

When I was first writing microlit, it wasn’t entirely embraced by poets or fiction writers in Australia – while I’d seen the term ‘prose poetry’ I don’t think I’d encountered the words ‘microliterature’ or ‘microlit’ and I was unfamiliar with ‘flash fiction’. When I’d submit to journals, the poetry editor would tell me to send my work to the fiction editor and vice versa. I managed – somehow – to write a novel called The Man Jar (Printed Matter Press, 2010) which was reviewed as ‘like Nabokov on speed’. Essentially that was a compliment for a book that, looking back, is way too exhausting for the reader. It’s microlit in a macro setting; mismatched forms and settings.

When I was first writing microlit, it wasn’t entirely embraced by poets or fiction writers in Australia – while I’d seen the term ‘prose poetry’ I don’t think I’d encountered the words ‘microliterature’ or ‘microlit’ and I was unfamiliar with ‘flash fiction’. When I’d submit to journals, the poetry editor would tell me to send my work to the fiction editor and vice versa. I managed – somehow – to write a novel called The Man Jar (Printed Matter Press, 2010) which was reviewed as ‘like Nabokov on speed’. Essentially that was a compliment for a book that, looking back, is way too exhausting for the reader. It’s microlit in a macro setting; mismatched forms and settings.

- As a critic and academic, you have been thinking and writing about the microlit form for some time now. You recently presented a paper on microlit at the MIX 2017 Writing Digital conference at Bath Spa University and contributed a chapter on the form in a forthcoming publication in Axon: Creative Explorations Can you give our readers a potted history of the form and a sense of how it is viewed by literary theorists?

I find microlit fascinating. Many writers engage with the form at some point in their writing lives and, when they do, they realise what a chameleon it is. As a short form, it also often has the advantage of being disseminated further than longer forms for the simple reason of its brevity and portability. For example, a prose poem or piece of flash fiction mostly appears as a paragraph or series of short paragraphs on the page or screen. Microlit can be read on social media, on artworks, on posters and it tends to appear quite innocuous – so that a reader will wander into it and start reading before they realise that, as a compressed form, it is opening out to embrace all kinds of references, ideas and experiences. In this way, microlit can actually be a brilliant form for activism and allow poets and short fiction writers to engage as public intellectuals if they choose to use the form to lobby for something significant.

The best writers are readers and so I started reading as much prose poetry and theory on the short form as I could lay my hands on. And I realised there wasn’t a huge amount of theory published critically on microlit. Robert Shapard is one of the most interesting writers on short fiction and he has a compelling piece in World Literature .

However, anthologies are probably the best place to find a range of microlit and they often have really useful introductions which attempt to explain or identify aspects of the form. While there are some scholarly books and a growing number of articles on specific aspects of prose poetry (see Axon:and Text:), there is no book that is the definitive text for this form. For this reason, my colleague, Paul Hetherington and I are currently writing a book on prose poetry for Princeton University Press, after writing a series of journal articles together on the form. We make the point that contemporary manifestations of the prose poem has a complex history dating back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – and even earlier if you include as a kind of prose poetry the late seventeenth-century Japanese development of the haibun.

Here’s an excerpt from one of our draft chapters:

The contemporary form of the prose poem became established in the mid-nineteenth century when it was invented by a variety of groundbreaking French practitioners [including Baudelaire, Rimbuad and Mallarmé] … Such writers developed the prose poem as a new literary form in opposition to both the conventional and rather inhibiting neoclassical rules of French prosody that required poets to follow particular metrical, rhythmic and rhyming patterns, and also as a development of the French tradition of the so-called poème en prose; usually extended works of poetic prose, which – not always successfully – had already tried to make a break both with neoclassical poetic forms and the prose novel.

We make the point that the contemporary prose poem should be considered a product of nineteenth-century Romanticism (see article here) rather than of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and that in the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries, the prose poem has evolved in so many directions in various countries, and prose poets have done so many different things with the form, that it is difficult to generalize about all of its developments.

The one question I am asked quite a lot is whether prose poetry is a genre or form and if it’s fiction or poetry. In my opinion it’s a form of poetry (poetry is a genre). Charles Simic’s success in winning the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1990 was a significant moment in sorting out this kind of categorization. A better question may be whether precise categorization is necessary. There are now a plethora of hybrid and neo-experimental literary forms, so the definition of particular and separate forms is increasingly tricky.

- You have judged The joanne burns Microlit Award for the past two years and you are series editor for the annual Spineless Wonders microlit anthology. How does this experience compare to the other editorial roles you have had? How do you approach the task of assessing microlit?

In the last few years, in addition to judging the joanne burns award and editing the Landmarks and Time anthologies for Spineless Wonders, I’ve judged the Victorian Premier’s Prize, the Lord Mayor’s Prize for Poetry, Australian Book Review’s Elizabeth Jolley short story award and edited or co-edited editions of Australian Poetry Journal, Cordite Poetry Review, Rabbit – a journal for nonfiction poetry, Mascara Literary Review and I’m currently the poetry editor of Westerly (this is my final year in that role and I’ve loved it!) From these experiences I can say that I prefer judging blind. While I may occasionally recognise someone’s work from the voice or style of the writing, with the majority of pieces I read I have no idea if the writer is emerging or established; if they’ve had no work published or ten books – and I like the way this evens the playing field.

Judging awards and competitions, and editing or curating journals are some of my favourite things to do. It is a wonderful opportunity to see what people are writing and how they are writing it. You can identify trends and see things that work and don’t work, especially in the short form. For instance, one year I judged a short story competition and there seemed to be a trend for writing dystopian narratives. The next year I judged a poetry competition and lots of entries were written about public transport – trains, in particular! I think the lesson from this experience for a writer, is to try and think ahead to find something outside what everyone else is thinking about – to try and pre-empt the next trend or be entirely outside of it. It’s no good writing another Game of Thrones or vampire narrative! Or applying this to the short form, it’s no good copying Lydia Davis or James Tate, you need to find your own ideas and style.

I can be a bit of a heavy-handed editor. This is because I believe the works I choose reflect on me as an editor, as well as the writer. So, I like to think that each piece of writing I select is the very best it can possibly be. Sometimes that means I edit out some adverbs or adjectives (or kill people’s darlings, as they say) and I think from working in the short form I’m invested in good opening and concluding lines – so I often ask for them to be tweaked by the writer if they aren’t working as well as they could be.

I love it when a publication I edit has a theme because it gets writers thinking in fascinating ways about related ideas and demonstrates how differently people tackle related concepts. It also gives writers a focus. The Landmarks and Time anthologies and the Cordite ekphrastic issue that I co-curated, are excellent examples. When there is a theme for writers it is always important that the approach or reference to the theme is not too obvious or clichéd. For example, ‘time’ was explored by writers in a d pieces about history, jetlag and the refugee crisis.

I love it when a publication I edit has a theme because it gets writers thinking in fascinating ways about related ideas and demonstrates how differently people tackle related concepts. It also gives writers a focus. The Landmarks and Time anthologies and the Cordite ekphrastic issue that I co-curated, are excellent examples. When there is a theme for writers it is always important that the approach or reference to the theme is not too obvious or clichéd. For example, ‘time’ was explored by writers in a d pieces about history, jetlag and the refugee crisis.

Microlit is my favourite form for judging, reading, selecting and editing (as well as writing). This is because I have the luxury of reading entries many times over and re-reading not just parts of them, but the works in their entirety. That’s not always possible when I’m judging novels and long short stories. I like to longlist and then shortlist entries and finally narrow it down to a top five. This process happens over many weeks and I keep colour-coded spreadsheets to help me. Most importantly, I like to see writers who understand microlit and who have clearly read a lot of it, and a lot about it. An easy example is that microlit shouldn’t just be a longer story or poem crushed into a smaller space.

- Microlit, micro/ flash/sudden/postcard fiction. What’s the difference and does it matter?

I think microlit is a good umbrella term for very short fiction (in all its forms) and all kinds of prose poetry. What is particularly interesting is the way that microlit anthologies and a blog like Sudden Prose place these short forms of poetry and fiction in juxtaposition. So, it’s not about labelling some pieces ‘prose poetry’ and others ‘flash fiction’, it’s about enjoying microlit in all of its incarnations. Perhaps some readers would disagree if you asked them which pieces are flash fiction and which pieces are prose poetry and I’m not sure in this instance it always matters.

- You once commented in a review of Best Australian Stories (Black Inc) that “It is disappointing that there is no flash or mico-fiction” in this Australian anthology. How do you think the short-short story form is currently faring in Australia? Is there a distinctive Australian version of the form evolving? If so, what are its qualities?

Microlit is Australia is flourishing and it is slowly getting the attention it deserves. Now, many Australian writers include prose poetry and flash fiction in their collections and microlit in anthologies continues to grow, legitimising it as a popular form in Australia. One way of tracking the popularity and respect for the short form is in the ‘Best Australian’ anthologies each year. I think it’s interesting that prose poetry is included in Best Australian Poems but flash fiction and very short forms like flash, are not as popular in Best Australian Stories – as the quotation from my review in Australian Book Review indicates. It’s exciting to see such a rich and textured form demand attention. Spineless Wonders is one of the few Australian publishers devoted to encouraging its growth by giving it centre stage in competitions, festivals, installations, microlit videos, poemfilms and publications and the slick and savvy online journal, Seizure, offers itself as the ‘online home for Australian flash fiction’. It’s a wonderful addition to Australian literary journals and magazines for its focus on the very short form and I love the way the title cheekily references the way flash fiction is able to seize a moment, as well as constitute a kind of rupture. I also want to mention Slow Canoe which has now started producing chapbooks of its performances and celebrates the short form in both fiction and nonfiction.

…contemporary culture requires such literary forms [as microlit] in order to speak truthfully about the crises at the heart of modernity centred on identity, the interpenetration and mixing of cultures and the need to find authentic ways of speaking..

Overall, I think Australian writers are increasingly making use of narrative and poetic forms that do not sit comfortably within accepted genre classifications, such as microlit. I’ve co-written a paper about this which argues that they are doing so partly in order to respond to their encounters with fragmentation and multivalency and to register the disparate, the diverse and the ‘broken’ in postmodernity. It is possible that contemporary culture requires such literary forms in order to speak truthfully about the crises at the heart of modernity centred on identity, the interpenetration and mixing of cultures and the need to find authentic ways of speaking. By doing this I think it challenges assumptions about what may be ‘said’ in writing, and whether much of human experience in the 21st century may best be expressed through the creation of ‘in-between’ literary spaces (and associated tropes of absence and indeterminacy), rather than through traditional generic models. Australian microlit prioritises spaces of uncertainty and anxiety to rework the British and American canon and make its own identity. It can also manifest itself in microlit that has a laconic and black humor which is distinctively Australian in its expression of the uncanny.

- You judged the recent joanne burns Award entries while on holiday in Japan, a place you visit often. Why Japan? Do you see any parallels between microlit and Japanese culture?

Japan is full of tiny things and the Japanese place enormous value on things that are small. For example: there are tiny bars and restaurants in Japan that seat as few as 3 people; the Japanese mostly drive tiny cars; they often live in small apartments, and while I’m too claustrophobic to try them, there are capsule hotels. There’s been a lot of discussion about whether this comes from Buddhist minimalist or the lack of space in Tokyo, for instance. I like to think it’s because the Japanese are more aware of the beauty in the small; they don’t go for large, vulgar things. While I have often lamented the tiny cocktails and tiny diamond jewellery in Japan (no doubt exposing my Western vulgarity), I admire the way that these values about the tiny – and what others consider insignificant –are connected to wabi sabi (or the focus on transience and imperfection) and, to some extent, the cult of kawaii (or cute), which I enjoy.

Japan is full of tiny things and the Japanese place enormous value on things that are small. For example: there are tiny bars and restaurants in Japan that seat as few as 3 people; the Japanese mostly drive tiny cars; they often live in small apartments, and while I’m too claustrophobic to try them, there are capsule hotels. There’s been a lot of discussion about whether this comes from Buddhist minimalist or the lack of space in Tokyo, for instance. I like to think it’s because the Japanese are more aware of the beauty in the small; they don’t go for large, vulgar things. While I have often lamented the tiny cocktails and tiny diamond jewellery in Japan (no doubt exposing my Western vulgarity), I admire the way that these values about the tiny – and what others consider insignificant –are connected to wabi sabi (or the focus on transience and imperfection) and, to some extent, the cult of kawaii (or cute), which I enjoy.

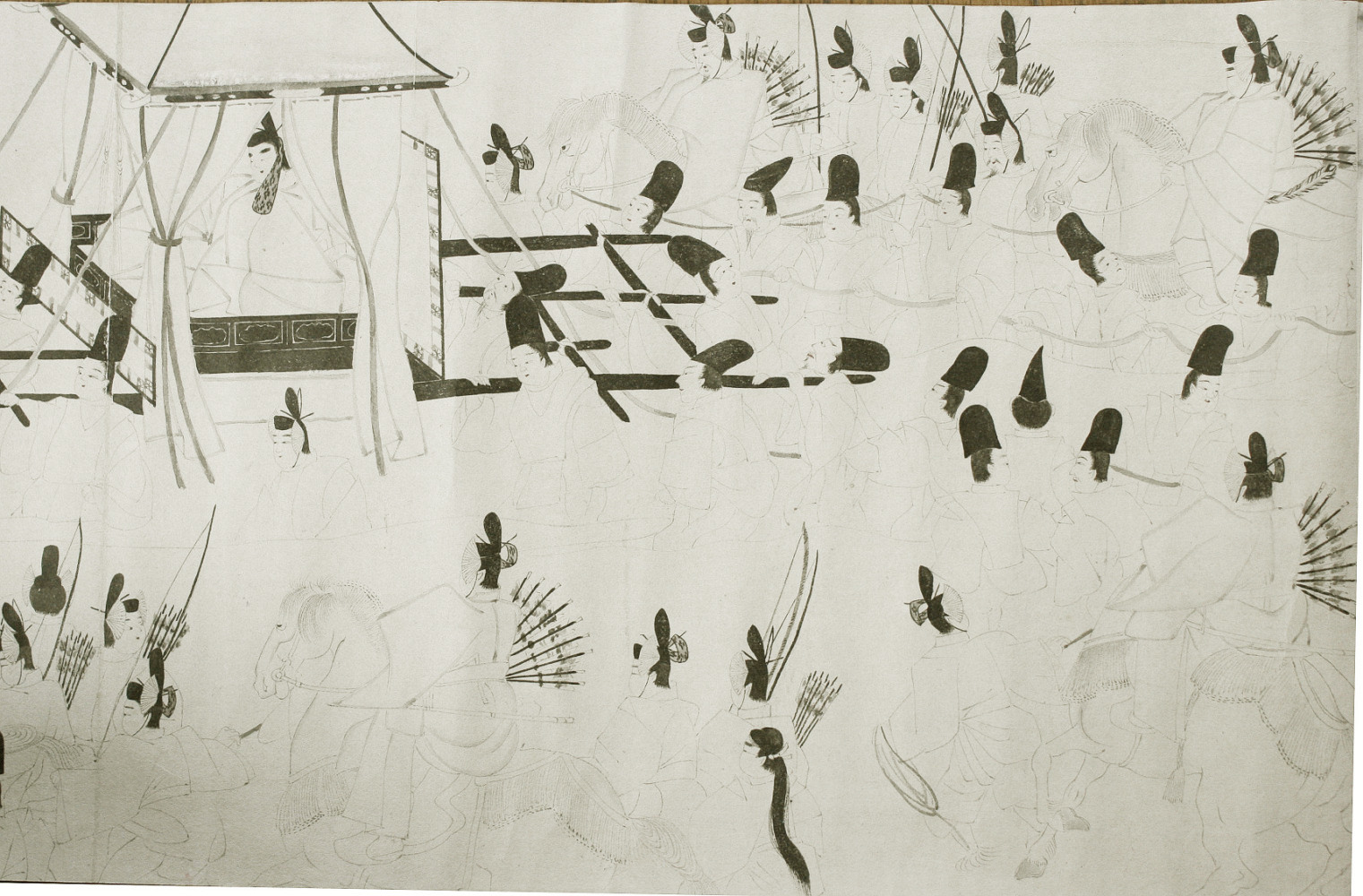

Of course, more obviously, both the haibun and the pillow book are Japanese and are forms of microlit. (The feature image for this interview is part of one section of the Illustrated handscroll of The Pillow Book, ink on paper, 13th century, Japan Published ACE1921. Copyright free image.) Indeed, haibun has been identified as a form that combines the prose poem with haiku:

The result is a very elegant block of text with the haiku serving as a tiny bowl or stand for the prose poem. A whole series of them in a manuscript look like neat little signs or flags—a visual delight. (More here )

The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon is a loosely connected set of anecdotes, poems and description of moments in her life – it can be identified as a collection of microlit.

Finally, when I go to Tokyo, I often go to the Studio Ghibli Museum in Mitaka. One of the highlights is the very short film that is shown in the auditorium there. My favourite is called Mr Dough and the Egg Princess. The very short films remind me of poemfilms and microlit videos in their rich poetry and texture. The narratives are intense and beautiful, bursting open to encompass galaxies or enchanted worlds. Here is a fascinating look at the making of the latest one by Miyazaki called: Boro the Caterpillar (Kemushi no Boro):

Finally, when I go to Tokyo, I often go to the Studio Ghibli Museum in Mitaka. One of the highlights is the very short film that is shown in the auditorium there. My favourite is called Mr Dough and the Egg Princess. The very short films remind me of poemfilms and microlit videos in their rich poetry and texture. The narratives are intense and beautiful, bursting open to encompass galaxies or enchanted worlds. Here is a fascinating look at the making of the latest one by Miyazaki called: Boro the Caterpillar (Kemushi no Boro):

- The joanne burns Microlit Award is run in partnership between Spineless Wonders and the Newcastle Writers’ Festival. Tell us about your experience of working with this regional literary festival.

The Newcastle Writers Festival is wonderful for its recognition and celebration of microlit, alongside some of the more traditional forms of writing. Not only has the winner of the joanne burns award been announced at this event for the last two years, the festival has an amazing array of events focused on the short form. I chaired a panel on microlit last year and I’m delighted to chair another panel this year. Last year the #storybombing events were an incredible highlight. I loved Pavement Pages, an installation consisting of twenty 200-word microlit texts printed on the pavers using temporary paint. The layout of the pavers presented natural pathways between the ‘pages’ and allowed large numbers of people to wander from story to story, reading from different angles. Audio recordings of the microlit ‘pavement pages’ were accessed using Augmented Reality technology which viewers accessed via a free and simple to use mobile app. Basically, QR codes. Below is an example of one of the Pavement Pages audio which festival-goers could listen to on their smart phones via the QR code. [You can listen to all fifteen Pavement Pages, here on Soundcloud, Ed.] It was exciting to see so many people interact with the microlit in so many new and exciting ways.

The Newcastle Writers Festival is wonderful for its recognition and celebration of microlit, alongside some of the more traditional forms of writing. Not only has the winner of the joanne burns award been announced at this event for the last two years, the festival has an amazing array of events focused on the short form. I chaired a panel on microlit last year and I’m delighted to chair another panel this year. Last year the #storybombing events were an incredible highlight. I loved Pavement Pages, an installation consisting of twenty 200-word microlit texts printed on the pavers using temporary paint. The layout of the pavers presented natural pathways between the ‘pages’ and allowed large numbers of people to wander from story to story, reading from different angles. Audio recordings of the microlit ‘pavement pages’ were accessed using Augmented Reality technology which viewers accessed via a free and simple to use mobile app. Basically, QR codes. Below is an example of one of the Pavement Pages audio which festival-goers could listen to on their smart phones via the QR code. [You can listen to all fifteen Pavement Pages, here on Soundcloud, Ed.] It was exciting to see so many people interact with the microlit in so many new and exciting ways.

Newcastle Writers Festival is a vibrant and intelligent meeting of writers and readers against the most amazing backdrop – I fell in love with Newcastle when I attended my first Newcastle Writers Festival last year. It’s so well organised with so many people there to help you find your way to and from events (I’m used to rushing around and getting lost at Writers Festivals!). Despite the large numbers of people there’s also an intimacy to the sessions which allows everyone to delve deeper into issues concerning contemporary writers and writing lives.

- And finally, a question about multi-platform storytelling. Many of the microlit pieces you have selected have gone on to have a life beyond the page as part of SW’s #storybombing and microlit video projects. What do you think about this?

The consensus is that new digital publishing ventures, and a surge of graduates from universities and writing centres, are creating impetus for the short form. With eReaders (by this I mean any mobile electronic reading device) becoming more popular, our reading habits are changing, and we’re discovering the strengths of mobile formats. Renewed interest in short-form work is a reflection of that shift – and in Australia, some even credit the success of US writer Lydia Davis and Australian writer Maxine Beneba Clarke in winning significant literary prizes for short story collections in 2013 as evidence of that shift.

Digital publishing offers fiction and poetry writers more interactivity, more freedom-to-create, than paper publishing ever did. Currently the e-book in Australia is largely a paper book digitized, but the digital allows for greatly enhanced narratives and effects. In the future, the fiction writer and poet will be part of a different process – more like that of the script writer currently – a cog in a larger machine of production, but the initiating and major cog, just the same.

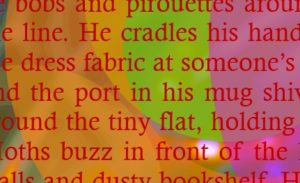

Public and digital outcomes for storytelling have the advantage of capturing new audiences, writers and readerships for microlit in unexpected ways. This is exactly what #storybombing aims to do. But perhaps more ambitiously, it focuses on the reader and attracting new and larger public readerships via digital engagement. Spineless Wonders’ #storybombing initiatives manage to make some important ground in this area. Richard Holt’s Flashing The Square Microlit videos (see still above), for instance, were created specifically for the passing audience of the public video space, with multiple points of engagement for viewers. The videos are visually dynamic without distracting from the text, which remains the focus. The engaging soundtrack and images bring the printed word to life making the videos an ideal medium for engaging both lovers of literature as well as new audiences.

Public and digital outcomes for storytelling have the advantage of capturing new audiences, writers and readerships for microlit in unexpected ways. This is exactly what #storybombing aims to do. But perhaps more ambitiously, it focuses on the reader and attracting new and larger public readerships via digital engagement. Spineless Wonders’ #storybombing initiatives manage to make some important ground in this area. Richard Holt’s Flashing The Square Microlit videos (see still above), for instance, were created specifically for the passing audience of the public video space, with multiple points of engagement for viewers. The videos are visually dynamic without distracting from the text, which remains the focus. The engaging soundtrack and images bring the printed word to life making the videos an ideal medium for engaging both lovers of literature as well as new audiences.

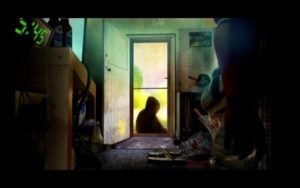

Indeed, videos and short films are an ideal medium for engaging both lovers of literature as well as attracting new and often younger audiences. This is why Spineless Wonders’ collaboration with the staff and students from the animation department of the University of Technology, Sydney to produce animated videos based on microlit, is especially interesting. See the above still from ‘The Apple Tree’ a student video based on Linda Cook’s microlit, ‘The Apple Tree’. Coupling microlit with video, film and/or animation allows us to hear, see, ‘read’ and internalize this form in new ways – ways that can elicit a profoundly creative response. Cross-media work appeals to people who are sound- or visually-driven, as well as those searching for a strong narrative element and a degree of sophistication in writing; it encourages new audiences, writers and readerships. The strength of any narrative is of key importance because it is essentially the ability of the writer to capture the reader’s interest and engagement in story.

Indeed, videos and short films are an ideal medium for engaging both lovers of literature as well as attracting new and often younger audiences. This is why Spineless Wonders’ collaboration with the staff and students from the animation department of the University of Technology, Sydney to produce animated videos based on microlit, is especially interesting. See the above still from ‘The Apple Tree’ a student video based on Linda Cook’s microlit, ‘The Apple Tree’. Coupling microlit with video, film and/or animation allows us to hear, see, ‘read’ and internalize this form in new ways – ways that can elicit a profoundly creative response. Cross-media work appeals to people who are sound- or visually-driven, as well as those searching for a strong narrative element and a degree of sophistication in writing; it encourages new audiences, writers and readerships. The strength of any narrative is of key importance because it is essentially the ability of the writer to capture the reader’s interest and engagement in story.

The short form is proliferating and it’s exciting to see it both in book form but also liberated from the page.

CASSANDRA ATHERTON is an award-winning writer, academic and critic. She is Associate Professor at Deakin University and is currently a Harvard Visiting Scholar in English. Her most recent books of prose poetry are Trace (Finlay Lloyd, 2015) and Exhumed (Grand Parade, 2015).

CASSANDRA ATHERTON is an award-winning writer, academic and critic. She is Associate Professor at Deakin University and is currently a Harvard Visiting Scholar in English. Her most recent books of prose poetry are Trace (Finlay Lloyd, 2015) and Exhumed (Grand Parade, 2015).