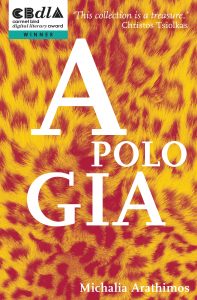

In this post, Bridgette Sulicich and Dahlia Mikha from Spineless Wonders ask our latest author, Michalia Arathimos about her award-winning short story collection, Apologia, about the challenges of tackling tough topics, about writing from different points of view and about the influence of her Greek heritage on her writing. In this fascinating and wide-ranging interview Arathimos quotes Zadie Smith, Christos Tsiolkas and reflects on some of the urgent issues facing contemporary writers.

Firstly, thank you for these excellent questions! It’s a pleasure to see interviewers who are so completely engaged.

- Many of the stories in Apologia deal with loss and displacement, what about these themes speak to you?

I’m a third generation Greek who has lived away from my place of birth for half of my life. I grew up inside the stories told by my family about their migration. It wasn’t until I learned the Greek word xenitia that I understood the sense of almost-nostalgia that informed their stories. Xenitia is a word that means a longing for home, and it’s a tangible part of the Greek diaspora. But that nostalgia has a romantic aspect to it: it can mean a longing for another time, for an ideal, or for a home that never really existed. My work is informed by this feeling of xenitia, this feeling of hopeless love for a place that culturally constitutes the idea of ‘home’, even though I was not born there.

- There are also quite a few references to psychological turmoil, reasoning and exploration, especially in An Appropriate Response and The Paper Bag. What were the challenges in writing about these topics?

In An Appropriate Response and The Paper Bag, the protagonists are struggling with specific forms of psychological turmoil caused by the iterations of capitalism and sexism.

Nicky Rose wears a fake leopard skin coat in the Byron Bay sun. When she strips off, parading in front of a group of rich men, her nakedness is a radical act. Her ability to celebrate her body is her salvation, but it looks like a mad response.

In The Paper Bag the main character is under pressure as a result of Western models of motherhood that require female-identifying people to perform most of the early childcare and housework, outside of traditional structures, while the male-identifying person works. Her turmoil is a reaction to the realities of capitalism, sexism, climate change anxiety, and violence towards women.

The challenge in writing about these characters was that I wanted the reader to understand how their ‘crazy’ actions are purely logical, in the end, not symptoms but triumphant responses to a flawed system.

The challenge in writing about these characters was that I wanted the reader to understand how their ‘crazy’ actions are purely logical, in the end, not symptoms but triumphant responses to a flawed system.

- You write from a vast array of perspectives; males and females of many different time periods, cultures and places. What is involved in your research for a character and their story, and how do you get into their headspace?

Writing is about consistency and discipline, not divine inspiration. But that doesn’t mean that ideas and characters are not magically visited upon you. They are.

Often for me the thread of a story develops over time, with the origin point being a phrase that catches my interest. When I wrote ‘The Highwaywoman’, the origin point was a poem published in a book, A Treasury of Childrens’ Verse, which was given to school children in the nineteenth century. The poem really does depict murder, suicide, and potential rape, and it was given to children at school. When I read it I imagined a mother at that time, her concerns, her preoccupations, how in her world this poem was the right kind of education. When I came to writing the story I needed to research the details: what currency was in use in the Melbourne of that period, and when did the gold rush begin to fail?

Most of my characters though usually come from experiences that I have either had or been close to myself. In The Guardian, Christos Tsiolkas wrote that he:

‘… needed to give voice to the reality of the contemporary Australian suburb, one of high-street shops in which one can hear dozens of languages, populated by generations who have never felt an allegiance to a colonial British and Celtic history.’

My characters are from a variety of backgrounds, sexualities, and cultures, because that is the world I inhabit.

- How much has your Greek heritage influenced you as a writer?

As a white person, I have always ‘passed’ as part of a majority group in both Australia and Aotearoa. But as part of a migrant family I’ve had a sense of living a double life. Greeks are model assimilators, but we have another language, another religion, unbreakable links to ‘the homeland’. Such inborn displacements have made me question things like identity, belonging, and loss.

Growing up inside my culture was an education in the importance of story-telling. In repeating narratives, we make ourselves ‘us’. My heritage has made me aware of the arbitrariness of our positioning. Our stories can make us ‘us’, but if we aren’t careful, they can keep others out as well. In my writing I try to write stories along the borderlines, trying to show how problematic those borderlines are.

- Your stories tackle some very tough topics. How hard is it to write about traumas, especially those that you have not experienced yourself?

Zadie Smith controversially defended the right of authors to write about a range of people and subjects in an essay titled ‘Fascinated to Presume: In Defence of Fiction’. She writes:

‘…what insults my soul is the idea—popular in the culture just now, and presented in widely variant degrees of complexity—that we can and should write only about people who are fundamentally “like” us: racially, sexually, genetically, nationally, politically, personally. I do not believe that. I could not have written a single one of my books if I did.’

The danger inherent in this statement is that such notions can be co-opted into arguments that might attempt to justify someone writing from an indigenous point of view, for example, and having no connection with that culture. I think it’s particularly important when dealing with cultural trauma to have appropriate readers to ensure that you aren’t causing harm.

But Zadie Smith has a point. At one point I went through a crisis: If I only wrote from my own position, I could only write about Greek-New Zealand-born women of a certain age. Similarly, if I limited my fiction to covering only the exact traumas I myself had experienced, my subject matter would be narrow.

But in terms of the traumas experienced by characters in this collection, most of them are traumas that I have personally touched, whether in my own life, my families’ lives, or through close friends. I’m not sure that we can own trauma, but I think it’s important that if someone asks you about your right to right certain stories, you can speak to that. And I can.

- What was the most difficult piece in this collection to write, and why?

The Paper Bag. Because much of what I write looks like realism, but the elephant in The Paper Bag clearly pushes this collection into some other genre. This felt risky for me. In Bearing Witness there’s also an unexplained moment where Maria’s client ‘channels’ her dead father. This felt risky, too.

This ‘difficulty’, though is just part of my confusion in positioning myself as a writer. Nam Le has famously questioned the term ‘ethnic fiction’, in both his interviews and in in his fiction itself. The existence of something obnoxiously called ‘ethnic’ writing begs the questions: What is it, then? What does it look like? When I was growing up as a writer, it looked like magic realism. But the grittiness of what I write about has always been at odds with this.

But the elephant happened, so who knows what happens now.

- In Apologia there are threads of humour intertwined with historical tragedy (p. 63). How do you balance the tone of a story without one dominating the narrative?

The truth is that trauma exists, displacement exists, and famine and war and migration exist, but also things in general are sometimes pretty funny.

Just because someone has a history of intergenerational trauma, doesn’t mean they are not inadvertently hilarious. And just because we might have experienced tough times in our lives, doesn’t mean we are not self-aggrandising twits.

During my upbringing, a story about the fall of Constantinopoli might be interlaced with a slightly modified recipe for tiropita, and an infomercial for a footbath playing on the TV, and the tragedy would be no less tragic, and the funny stuff no less funny.

- Which aspects of your writing process most excite you?

First drafts. Everything else is work, satisfying, but work. But the first draft is just like falling, in a pleasant way.

Michalia Arathimos is a Greek writer. She has published work in The Lifted Brow, Westerly, Overland, Landfall and elsewhere, and is Overland’s fiction reviewer. Her novel, Aukati, was published by Makaro Press. She is the Writer in Residence at Randell Cottage and will hold the Grimshaw Sargeson Fellowship in 2021.

Michalia Arathimos is a Greek writer. She has published work in The Lifted Brow, Westerly, Overland, Landfall and elsewhere, and is Overland’s fiction reviewer. Her novel, Aukati, was published by Makaro Press. She is the Writer in Residence at Randell Cottage and will hold the Grimshaw Sargeson Fellowship in 2021.