1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

My favourites include Jhumpa Lahiri, Raymond Carver, Lorrie Moore and A.L. Kennedy. This year I read the best short story cycle I’ve ever read, Elizabeth Strout’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, Olive Kitteridge. It’s a portrait of the inhabitants of a small town in Maine as much as it is of the central character, Olive Kitteridge, who stars in some stories, while in others she is just talked about and in one story all that she does is wave to the jazz pianist. I loved it. As far as Australians go, I’m a big fan of John Murray’s A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies (Penguin, 2004). I don’t know if John is still writing short stories, but I hope he is. David Malouf’s Dream Stuff is a very strong collection.

2. What is the most memorable short story you have read? And why does it stand out for you?

There’s no way I can narrow it down to one. I love Jhumpa Lahiri’s “A Temporary Matter” in Interpreter of Maladies for the beauty of its prose, its heart-rending story of the end of a relationship and for its sophisticated use of one character’s point of view that effectively illuminates two people. James Baldwin’s “Going to Meet the Man” in the collection of the same name is probably the most powerful story I’ve ever read, but it’s also remarkable for its clever manipulation of time, Baldwin’s compassion for the story’s racist policeman and his gripping, visceral narration of violence. I love Raymond Carver’s “A Small, Good Thing” for the way the story of a baker and a family’s tragedy intersect. It captures both the sense of crippling alienation that living in a city has for many people, as well as delivering a way out of it. Although Gordon Lish did improve Carver at times, he certainly butchered much that was very fine and which is now available to us again. There’s no way that “The Bath”, Lish’s truncated version, is better than the emotional punch that “A Small, Good Thing” delivers. The first short story writer I fell in love with was Peter Carey, buying a hardback copy of War Crimes from the Ivanhoe newsagency when I was twenty. I can’t forget “Exotic Pleasures” with its addictive, evil birds or “American Dreams” with its scathing critique of tourism and the surprising twist at the end. Carey remains a giant of the Australian short story.

3. What do you like about the short story form?

What’s not to like. It’s a kick to the guts, an electric shock, a pure pulse of adrenalin. So much can be done within a short story, from uproarious comedy to captivating suspense. The short story can deal with multiple narratives as Lorrie Moore does in “Real Estate”, it can present one character in rich detail as Chekhov does in “A Boring Story”, it can mime the richness of a central metaphor as Tony Birch does in “The Sea of Tranquillity”. You can read it in an evening and if the story is top notch, then re-read it and still be hooked. Then there’s the strangeness that runs right through the form, from Herman Melville’s “Bartelby” to T.C. Boyle’s “Tooth and Claw”. I’m not sure why I love stories so much, it’s just something that’s happened gradually over the years as I’ve continued to read and write. One of the advantages of a short story is the way you can hold it all in your mind, which is not something I can do with most novels.

4. How would you describe your own writing?

Initially I wanted to write poetic prose like Michael Ondaatje and Toni Morrison and there are elements of that impulse in Under the Same Sun and in some of my early stories. But gradually I became much more impressed by writers who aren’t obviously show ponies, writers like Colm Tóibín, Pat Barker and J.M. Coetzee who write beautiful unadorned rhythmical prose that tells a story and sings in a quieter, less obvious manner. That’s what I now aspire for, but whether I achieve it or not is really for a reader to say. The other shift for me was from writing historically researched novels to a book of short stories that is largely contemporary, except for one story that cuts between a nineteenth century frontier Queensland narrative and a contemporary university setting.

5. Which of your stories are you most fond of right at this moment and why?

Probably “Old Friends” which was first published in The Sleepers Almanac No 4 http://sleeperspublishing.com/and will be in The Swarm (forthcoming from Puncher and Wattmann around July 2012). A friend of mine calls it the barbeque story, because the central character decides that in response to the dreaded question people ask, ‘So what do you do?’ he will just respond, ‘I barbeque, I’m a barbeque man.’ It’s partly about male identity, but it’s also about unrequited love, death and catching up with friends years later, when life hasn’t quite worked out as you thought it might when you were twenty. I tried to capture that sense of living in a contemporary world, when nothing much is resolved, when the protagonist is struggling rather than being hugely successful and just making the best fist of it he can. It’s a hopeful story, but the hope comes from the struggle, from just living.

6. Where do the ideas for your stories come from? (Take us through an example)

Probably different for every story. “Old Friends” came from the time I worked with actors producing audio books at Royal Blind Society and is partly inspired by hearing about their lives, but much of it is made up. I wrote “In my Arms” after hearing about people who lost their daughter in a swimming pool accident, but I never met them. Sometimes my stories are inspired by stories written by other writers, Jhumpa Lahiri for example. “The Fibbing Bird” came partly from the time I spent chopping and carting wood from two fallen trees in what was a jungle below our house, but the rest of it I made up. The first line of “Vanilla Malted”, ‘It’s the happiest day of my life when Tony brings this girl home’ I heard someone say at a wedding reception and that was enough to kick-start the story. Recently I’ve been playing around in poetry with bringing authors and fictional characters back to life, such as Raskolnikov, Captain Ahab and John Keats, and “The Elusive Tenant”* is driven by a similar impulse. It’s a surreal exploration of what might happen if you put Marc Chagall in St. Peters, Sydney, rather than St. Petersburg, in the late twentieth century. Chagall’s paintings were a central inspiration for that story.

7. What is your writing process – from idea to publication? (Do you go it alone or are others involved?)

Writing is a very solitary activity and you have to go it alone initially. But I’ve recently become very motivated when I showed work to people and I’ve decided to try to do that more often. After umpteen drafts you lose the capacity to experience the thing as a reader does, for the first time. Apart from that, my process involves starting somewhere and hoping that the thing will work and that I’ll end up with a story that hangs together. Trusting my instincts and my intelligence and just working at the thing. I used to have a lot of trouble finishing stories, but I’m slowly getting better at endings. I’m a big believer in the Alistair MacLeod method of putting the thing away for 6 months and then having another go at it. When it feels as if another person wrote the thing, then you’re in a good position to work on it and see it as a reader might. And MacLeod is another giant of the short story, so he must have been doing something right. Is there a better ending in contemporary fiction than the beautiful last paragraph of “The Boat?”

8. Do you feel the short story form is valued in Australia? What makes you say this?

I’d like to see more value given to the substantial, twenty page story. What is it with 3000 words? Why limit Australian short fiction to these abbreviated disappointments? The Americans provide places for writers to publish longer short stories and the results are there for all to see. The yearly Best American collections are almost always stronger than the Best Australian collections. This is partly due to population, but it’s also because more can be done in a longer short story and if done well, then they’re more satisfying to read. There’s more space for the writer to develop a story with emotional heft and more scope for a reader to become fully engaged with the story’s concerns. The length of a story should not be a major factor in whether it gets published and read; often stories need to be longer than a postcard to work effectively. In Henry James’s day, when writers made a living from short fiction, the average story length was 8,000 words. It would be good to move back in that direction. I realise there are sometimes constraints because of space, but thankfully even that seems to be changing with Australian Book Review’s Elizabeth Jolley competition now taking stories up to 5,000 words. Be great to see Spineless Wonders embrace the longer short story.

9. How do you feel about your work being published in non-print forms such as digital and audio?

Audio is great, I used to produce audio books so I’m a big fan of them. If people want to read from a screen then that’s fine by me, but I like to hold a book in my hands and smell the paper.

10. What advice would you like to offer Spineless Wonders?

Cultivate rich patrons and friends who can cook. Dream big. Just do it. I doubt that you really need any advice. Good luck!

Andy Kissane lives in Sydney and writes fiction and poetry. His first novel, Under the Same Sun (Sceptre, 2000) was shortlisted for the Vision Australia Audio Book of the Year. A book of short stories The Swarm will be published by Puncher & Wattmann in mid 2012. He has published three books of poetry, Facing the Moon, Every Night They Dance and Out to Lunch (Puncher & Wattmann, 2009), which was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Prize for Poetry. He has taught Creative Writing at four universities and runs writing workshops for schools and the community. He coaches basketball, barracks for the Brisbane Lions, and is busy regenerating a bush garden. http://andykissane.com

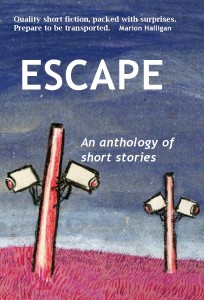

*Andy’s story, The Elusive Tenant, appears in Escape, the latest release from Spineless Wonders. Available for $24.99 from our website or ask your local bookstore for a copy.