1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

Some of my favourite contemporary Australian short fiction writers are Cate Kennedy, Nam Le, Helen Garner, Marion Halligan, Gillian Mears and John Clanchy. For the ‘otherwise’ who can possibly go past Alice Munro? And then there are the greats of the past, Chekov and Carver being two I admire most.

2. What is the most memorable short story you have read? And why does it stand out for you?

At the moment it’s Chris Womersley’s ‘Theories of Relativity’ which I first read back in March last year. It’s the unsettling and haunting tale of a dysfunctional and deeply troubled family. The story is beautifully constructed and written, with an arresting opening line: ‘You learn things in this life, don’t you, whether you like it or not.’ Every time I read ‘Theories of Relativity’ I am transfixed, compelled to read on to the brutal conclusion even though I now know what is coming.

3. What do you like about the short story form?

As a reader I like that I can finish a story in one sitting. On the bus, over a cup of tea, lying on the beach. There is a particular pleasure in that complete slice of time, and the best stories linger in the mind long after the last word has been read.

As a writer I like that I can complete a story quite quickly and that, unlike a novel, I can easily hold the whole thing in my head. I also like that the story is a glimpse into a larger world. The characters must be authentic, fully-formed, and the reader must be able to imagine that they have a life outside the brevity of the pages. A single word or sentence has the potential to suggest so much. There’s nowhere to hide in a short story. Every word counts. And a passage that doesn’t work will stand out, everything’s exposed. I enjoy that challenge. I recently heard Kate Grenville describe the short story as a bikini compared to the novel as a baggy overcoat. A wonderful analogy.

4. How would you describe your own writing?

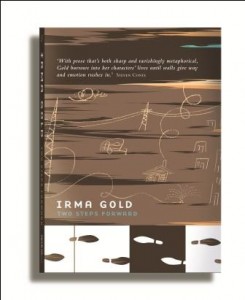

My stories explore the challenges and difficulties ordinary people face and their struggle towards some kind of happiness. Sometimes they get there, sometimes they don’t, and sometimes they discover an unexpected kind of happiness in the smaller things. Dean Gorissen, who illustrated and designed the cover of my new short fiction collection, Two Steps Forward, described my stories as being about the real Australia, the one ‘not in the tourist brochures’, which I think is true. There has been much debate since the announcement of this year’s Miles Franklin Award on how we define ‘Australianness’ in literature. The shortlisted books were all written by men that engage with the past in rural settings. All great books I might add, yet most of us live in cities. We seem to have got stuck with this rather antiquated and romantic idea of what represents Australian life. Yet so many writers are producing award-worthy stories that engage with our contemporary city-based lives. I, too, am interested in engaging and reflecting this world, focussing on people who manage to find light among the shadows.

5. Which of your stories are you most fond of right at this moment and why?

It’s difficult to choose, and my favourites are always changing. I think I have three that I’m equally fond of right now for different reasons, all from my collection Two Steps Forward. Creating ‘The Art of Courting’ was an immensely enjoyable experience. It’s written in second person and this allowed me to play with language in a particular way. It’s about a single woman in her forties who plays a series of flirtatious games with a man who moves into the neighbourhood. So the story itself has a sense of play and the language does too. It’s a joyous story, and I hope people share that feeling as they read.

In contrast ‘The Third Child’ is about a woman who loses a child to miscarriage. I wanted to write about miscarriage because as a society it’s something we fail to talk about, both at a public and personal level. It’s also an experience that is not represented well in literature or movies where we are mainly offered clichéd images of a woman clutching her stomach, a bit of blood, and then it’s all over. It’s rarely like that, so I wanted to write something that was authentic. I’ve had a lot of people – both men and women – tell me this is their favourite story in the collection.

And then there’s ‘Sounds of Friendship’, set in a caravan park. When I met Dean Gorrissen for the first time he told me that this story made him cry, and also that he thought I would look different to what I actually did, because he felt I must have direct experience of that world to write about it. This was really heartening for me. That I created a world that was so believable for him that he felt it must be autobiographical.

6. Where do the ideas for your stories come from? (Take us through an example)

In truth, I mostly have no idea where my stories come from. Sometimes it can be sparked by a snatch of dialogue I overhear (I think most writers are terrible eavesdroppers), or by a ‘character’ I come across, or a situation I encounter. An idea comes to me and I mull it over before consciously sitting down to write it. But mostly a story seemingly comes out of nowhere. I begin writing having no idea where it is going to take me. I feel like I am just following it, allowing it to unravel. And I love that process, that sense of discovery. For instance with my story ‘Tangerine’ an image came to me of a man and a young girl standing together on a platform in the middle of the night. They were ill at ease with each other, and I wanted to know why this was, and what they were doing on that platform. The story unfurled from there.

These kind of stories usually come in fits and spurts over a few days, often when I’m in spaces where my mind can freefall. I can be drifting into sleep or out walking or driving the car, when I have to suddenly switch on the bedside lamp or pull over the car and begin scribbling furiously.

7. What is your writing process – from idea to publication? (Do you go it alone or are others involved?)

I work very much in isolation to begin with. I don’t even talk about the story to anyone. It feels too fragile. As if a comment (even a positive one) could prevent the story from emerging in the right way. I work in both longhand and straight onto my laptop. Each story tends to be a mix of the two processes. As I write I’m always going back and editing. I suppose this is one of the perils of also being an editor. But while many writers see this as a negative (if you’re permanently editing you’re not getting on with the story), I find doing this kind of revision allows me to be suspended in the space of the story, thinking deeply – in both conscious and unconscious ways – about what will come next. Once I have a polished first draft I like to get editorial feedback, either from the short story group I am part of, or from other editors whose advice I value. I enjoy this refining process, working hard to make the story as good as it can be. Once I have completed several drafts I usually put the story aside for a few weeks. This allows me to come back to it fresh and see what else needs to be done. I know a story is finished when I go through it changing a word here, a comma there, and then on the next reading change them back again.

8. Do you feel the short story form is valued in Australia? What makes you say this?

It’s certainly valued by writers but readers don’t seem as taken with the form. And yet it seems to me that the short story is perfect for our time-poor modern existence. Then again they demand a great deal from their readers. Short stories are dense, they are closer to poetry than they are to the novel. Publishers don’t like them either because they think they’re economically unviable. Yet it does seem that the form is slowly regaining some favour, inch by inch. The success of books like Nam Le’s The Boat and Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad and Steven Amsterdam’s Things We Didn’t See Coming have demonstrated that a collection can attract a large readership. Let’s hope this gentle trend continues.

9. How do you feel about your work being published in non-print forms such as digital and audio?

There are now so many different ways for readers to access stories. I’m all for any medium that gets stories out there.

10. What advice would you like to offer Spineless Wonders?

Well done for supporting the fabulous but underappreciated short form. Continue to be bold and brave!