What happens when the visual and the verbal meet – when creatives working in different disciplines put their heads together? We talk with authors Jen Craig and Patrick Lenton and artists Bettina Kaiser and Daniel Lethlean Higson about the collaborative processes behind our upcoming releases A Man Made Entirely of Bats and Panthers and the Museum of Fire.

Jen Craig, author of Panthers and the Museum of Fire (SPINELESS WONDERS, MARCH 2015)

Q1. Have you been involved in collaborative projects before this one? Tell us about those briefly and in what ways they may have prepared you (or not) for this one.

Many years ago I was involved in a collaboration that went the other way around – I was the one producing illustrations for a book of poetry with Redress Press. I can’t remember much about the process, but I do remember having fun with what the poems suggested to me. Around that time I often worked with or, should I say, after poets and short story writers, to produce illustrations for Sydney University publications such as the Union Recorder and Hermes.

Since then my only collaborations have been with composers, both with my partner Stephen Adams (on a number of small projects), and with the Swiss composer, Michael Schneider, on a chamber libretto that had its first performance in 2005. For this chamber libretto, Michael had simply handed me The Surgeon of Crowthorne, by Simon Winchester, and said: can you write an opera based on this? So I read it. But I didn’t want to set the book as it was. As well as there being rights to worry about, there were also problems with the story itself because, apart from a few moments of high drama, such as the famous paranoid shooting murder on the streets of London and, later, the main character’s autopeotomy (I suggest you look up that word!), the book mostly concerned itself with elaborate speculations about the moment the dictionary editor realised that he wasn’t dealing with an eminent contributor after all but only one of his madder patients. So I did some research and decided to bring in another character, John Ruskin, and to form the libretto out of an interaction that Ruskin and the mad inmate of Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum, W. C. Minor, might have had sometime after the main event s of Winchester’s book. But I needed to negotiate this with Michael first. The trouble was that Michael had initially only wanted one singer for his chamber opera: W. C. Minor. But, luckily, he was easily talked around. Our only difficulty during the process of collaboration was the very long time – a great deal of back and forthing – that we spent trying to find a title we both could agree on (it is called A Dictionary of Maladies). After I finished the libretto, Michael took five years to write the music. I really didn’t know what kind of music he would produce. This part of it wasn’t collaborative – after all, it was Michael’s project in the first instance – although he did send me each scene as it was finished. The whole piece has had one concert performance in Switzerland and, as is the wont of Swiss new music productions (I gather), we were both interviewed for the German speaking audience beforehand, with the interviewer translating my English as we went. One of the questions we were asked was whether we would collaborate with each other a second time. Michael responded, but only in German, so I couldn’t understand what he said. When it was my turn to speak, I said first (in English), that my answer depended on what Michael had just said. Everybody in the audience laughed – clearly they’d understood enough English to get my joke. But since the interviewer still didn’t translate Michael’s response for me, I ended up having to say my bit in a vacuum. Later, when I asked Michael about it, he told me that he’d said he would be very happy to collaborate again but, since I worked faster than he did, he would need to have a bit of a breather first.

s of Winchester’s book. But I needed to negotiate this with Michael first. The trouble was that Michael had initially only wanted one singer for his chamber opera: W. C. Minor. But, luckily, he was easily talked around. Our only difficulty during the process of collaboration was the very long time – a great deal of back and forthing – that we spent trying to find a title we both could agree on (it is called A Dictionary of Maladies). After I finished the libretto, Michael took five years to write the music. I really didn’t know what kind of music he would produce. This part of it wasn’t collaborative – after all, it was Michael’s project in the first instance – although he did send me each scene as it was finished. The whole piece has had one concert performance in Switzerland and, as is the wont of Swiss new music productions (I gather), we were both interviewed for the German speaking audience beforehand, with the interviewer translating my English as we went. One of the questions we were asked was whether we would collaborate with each other a second time. Michael responded, but only in German, so I couldn’t understand what he said. When it was my turn to speak, I said first (in English), that my answer depended on what Michael had just said. Everybody in the audience laughed – clearly they’d understood enough English to get my joke. But since the interviewer still didn’t translate Michael’s response for me, I ended up having to say my bit in a vacuum. Later, when I asked Michael about it, he told me that he’d said he would be very happy to collaborate again but, since I worked faster than he did, he would need to have a bit of a breather first.

From all this I learned that collaborations are most fun and also most fruitful when you allow yourself to step forwards into the completely unknown aspect of the project – that is, when you say yes, but don’t even know what you have just said yes to. When everything is unsettled and very unknown. When I did all those illustrations for the Union Recorder, I grew to look forward to that small frisson, that spark, that I would get when I read the poem or story I was to illustrate, because I knew that this spark was the most important part of the process – that my best illustrations came from these very unintellectual, intuitive origins. This prepared me for the unknowing part of the collaboration, and for the sudden switch when, seeing the other’s contribution, you are surprised into either an instant recognition or a quiet reassessment of what you were unconsciously hoping to see.

Q2. Describe the stages in the collaboration from your point of view. Was it like a dialogue between two creatives? Or did the artwork stem from words on the page alone? Did you learn something new – about your own artistic practice or about the other artform?

Bettina and I met in her studio before she had read a single word of my novella. Actually, I lie: she knew the title. The whole process was born out of a conversation, and not just a conversation between Bettina and me. It was Bronwyn Mehan’s idea to have illustrations interleaved in the novella, and when I said I liked the idea, she organised a meeting between the three of us: Bettina, Bron and me. In this first meeting, we just talked, and I got to see the kind of work that Bettina did. She showed me some of her previous book cover designs, as well as some of her paintings and drawings. At the time she was involved in a Facebook group  whose members posted informal illustrations responding to their immediate everyday environments. I really liked the freedom and intimacy of these works. We talked about an approach to the collaboration: I was to send Bettina some chunks of text at intervals so that she could have something to work from. Bettina knew about the major action of the book – that is, the walk from Glebe to Surry Hills, and its exact route – but apart from that, she just had these snippets that I sent her. The first lot of illustrations she showed me were very diverse, which was helpful as it prompted me to identify what I was most looking forward to in the illustrations. As the collaborative process developed, Bettina seemed to be more and more cautious about her role. She told me she didn’t want her illustrations to take over my text (I think those were her words) and wanted me to understand that, if I didn’t like the illustrations or wanted to change my mind about having them at all, she would be very willing and happy to bow out. While I was thankful that she made it so easy for me to do this if I needed to, I never for one instant thought I’d change my mind about having her illustrations alongside the text. I trusted her. Bettina produced her second and final lot of images after she and her family did a second walk along the Panthers route, and these latest series of images were astonishing. They were perfect. I could see that, although Bettina hadn’t read the whole piece, she had nonetheless divined the nature of the voice – its obsessive and very inwardly oriented character. I then realised that somehow, in all of this, we had managed to communicate something between us that we had never, until after all these pieces had been made, put into words. It was as if the whole process had relied on something that was in fact quite wordless and imageless at its base – on something that was little more than a feeling. A resonance. So, even though our collaboration was indeed a dialogue between two lines of creativity – word making and image making – I can see we were both relying on something else to make it work. Without any awareness of this difficult-to-describe dimension, the collaboration could well have looked to observers to be just a one way shuffle since, clearly, the words pre-existed the collaborative process and were probably never going to change in response to the images.

whose members posted informal illustrations responding to their immediate everyday environments. I really liked the freedom and intimacy of these works. We talked about an approach to the collaboration: I was to send Bettina some chunks of text at intervals so that she could have something to work from. Bettina knew about the major action of the book – that is, the walk from Glebe to Surry Hills, and its exact route – but apart from that, she just had these snippets that I sent her. The first lot of illustrations she showed me were very diverse, which was helpful as it prompted me to identify what I was most looking forward to in the illustrations. As the collaborative process developed, Bettina seemed to be more and more cautious about her role. She told me she didn’t want her illustrations to take over my text (I think those were her words) and wanted me to understand that, if I didn’t like the illustrations or wanted to change my mind about having them at all, she would be very willing and happy to bow out. While I was thankful that she made it so easy for me to do this if I needed to, I never for one instant thought I’d change my mind about having her illustrations alongside the text. I trusted her. Bettina produced her second and final lot of images after she and her family did a second walk along the Panthers route, and these latest series of images were astonishing. They were perfect. I could see that, although Bettina hadn’t read the whole piece, she had nonetheless divined the nature of the voice – its obsessive and very inwardly oriented character. I then realised that somehow, in all of this, we had managed to communicate something between us that we had never, until after all these pieces had been made, put into words. It was as if the whole process had relied on something that was in fact quite wordless and imageless at its base – on something that was little more than a feeling. A resonance. So, even though our collaboration was indeed a dialogue between two lines of creativity – word making and image making – I can see we were both relying on something else to make it work. Without any awareness of this difficult-to-describe dimension, the collaboration could well have looked to observers to be just a one way shuffle since, clearly, the words pre-existed the collaborative process and were probably never going to change in response to the images.

Q3. Which parts of the collaboration were most enjoyable and which the most challenging?

The most challenging part was the very beginning of the collaboration – when I had to think about what kinds of illustrations I might prefer. This was challenging because all my ideas were very spare, plain and cautious – after all, I had never envisaged any illustrations going with the novella when I was writing it. Perhaps, if I’d been pressed, I might have said I didn’t think the story needed them. I was also very anxious. Even though I’d had some experience, as I have already said, with word-image collaboration, it had all been from the other way around, and so I had a strange, and quite inexplicable anxiety that I might be expected to direct things. The most enjoyable moments were when Bettina sent me her ideas or passed on her observations about what she’d read because her engagement with my writing seemed to be exactly on par with those moments when, as you are writing, you start uncovering something that seems to have always been there but never, until that moment, been on view – and certainly not anticipated or planned – that blessed moment that makes a fundamental difference to the direction and form of your entire piece.

Q4. What do the artistic works bring to the book?

Bettina’s images bring something lighter but also much more tangible to the book. The cover brings humour, great lashings of humour, and as for the illustrations: I think they harness the book and yet at the same time hold it suspended, and so harness it lightly. This is ironic, really. The images are so downwardly directed, so concentrated, almost blinkered – they anchor us to the ground – but, in working this way, they allow the text to move and bob as it will.

Q5. Would you take part in any future collaborations of this kind? Why?

Yes, of course. I am always curious about what happens in these kinds of collaborations, and my curiosity will always, inevitably, draw me in.

Bettina Kaiser, cover and photographs, Panthers and the Museum of Fire

Q1. Have you been involved in collaborative projects before this one? Tell us about those briefly and in what ways they may have prepared you (or not) for this one.

In my practice as a designer and artist I have worked on several collaborative projects over the past two decades. In music theatre set design, installation projects, as well as design projects where I was paired with artists or developers many of whom I had not previously worked with.

I learnt that being precious or having an ego has no place in this. Collaboration to me means to trust in the process, to trust the other side and most of all to be open – open to ideas, different ways of thinking, questions, exploring, changing, discussing. I believe two or more creative heads put together, are in the best circumstances, exponentially better than just one.

Q2. Describe the stages in the collaboration from your point of view. Was it like a dialogue between two creatives? Or did the artwork stem from words on the page alone? Did you learn something new – about your own artistic practice or about the other artform?

Bronwyn Mehan brought Jen Craig and me together in my studio. I had previously designed covers for Spineless Wonders. Bronwyn also knew that I had been walking a lot in the past year and occasional had posted about that on social media and shared photos of random finds on the way. Bronwyn thought these could fit really well with Jen’s story that takes place during a long walk, told as a stream of consciousness. She brought Jen and me together to put forward the idea to consider having some work by me illustrate, or more accompany, Jen’s work along the way.

Jen’s book was a finished work and at that stage just in the editing process. I was conscious that I did not want to interfere, or distract from the work by putting “my thing”, my visuals next to it. But Jen surprisingly was very open to the idea, maybe because I made it really clear that I wanted her to be able to have the final say and that we did not have to have illustrations at all if we have any sense that they may not work.

I checked in with Jen frequently throughout, to make sure she really was into the idea and the works that eventuated, and for them to become part of her published words. This was especially after a conversation with my husband Jon Steiner, who also writes short stories, who pointed out that a writer who just completed a major work would want to be pretty choosy about any illustrations selected to go with this work. Jen made it clear that she enjoyed my work, that she trusted me and the process and she gave feedback along the way.

I did the walk that spans the book 3 times over a few months. I read excerpts of the story, walked, stopped, drew, and later took photos. I shared my thinking and ideas along the way, which I think was important in winning Jen’s trust.

Q3. Which parts were the collaboration were most enjoyable and which the most challenging?

I most enjoyed meeting Jen, a fellow creative, and her openness and trust in the collaboration.

The biggest challenges were in my own head: perfectionism (should I have done the walk 20 times? taken more photos? retouched them? are they good enough?) and fear (of compromising or distracting from Jen’s work).

Q4. How does the context of this publication impact on your artwork?

I have taken near abstract photographs of details by the wayside for a long time now. They also tie in with my past abstract painting practice. For Jen’s book after trying a few different approaches (including drawings) I found them to be a perfect match. My selection was not only visually, as it usually would be, but very much with keeping the flow of the story in mind.

Q5. Would you take part in any future collaborations of this kind? Why?

Any time! I love creative challenges, and as mentioned earlier think that artists together can produce even richer, even more amazing things, than they can individually.

Patrick Lenton, author A Man Made Entirely of Bats (SPINELESS WONDERS, MARCH 2015)

Q1. Have you been involved in collaborative projects before this one? Tell us about those briefly and in what ways they may have prepared you (or not) for this one.

I’ve worked on LOTS of collaborative projects, mostly with my theatre company Sexy Tales Comedy. One of our plays ‘100 Years of Lizards’ was written during a collaborative residency on Cockatoo Island, pairing me as the writer with actors, musicians and designers to help come up with something truly insane. It definitely taught me that inspiration can come from any angle with so many different types of creative points of view.

Q2. Describe the stages in the collaboration from your point of view. Was it like a dialogue between two creatives? Or did the artwork stem from words on the page alone? Did you learn something new – about your own artistic practice or about the other artform?

I was happy for Daniel to take inspiration from the book, and it was illuminating to discover the things he focused on, the images that he drew from the stories.

Q3. Which parts were the collaboration were most enjoyable and which the most challenging?

It was all completely enjoyable and stress free!

Q4. What do the artistic works bring to the book?

It’s such a privilege to have someone else’s artistry combined with my work – the fact that someone took the time to read and be inspired or influenced by my own work is an amazing feeling.

Q5. Would you take part in any future collaborations of this kind? Why?

Absolutely – I think the art in the book helps make it more of a beautiful artefact that people will be happy to have on display on their bookshelves.

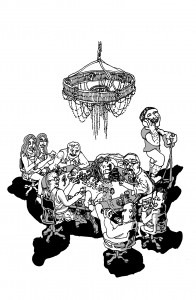

Daniel Lethlean Higson, cover and illustrations, A Man Made Entirely of Bats

Q1. Have you been involved in collaborative projects before this one? Tell us about those briefly and in what ways they may have prepared you (or not) for this one.

I’ve collaborated with visual artists before and have been directed by writers and musicians for design work but this is the first time collaborating with someone from a different discipline. I think past design work has made me learn flexibility within my own practice so that it can be made to fit with different situations. So that’s helped with being able to apply what would otherwise be a personal drawing practice, but this project was great because I had few restrictions and fun content to go off.

Q2. Describe the stages in the collaboration from your point of view. Was it like a dialogue between two creatives? Or did the artwork stem from words on the page alone? Did you learn something new – about your own artistic practice or about the other artform?

I got a sense of the direction that Patrick was envisaging but from there on I worked wholly from the stories. It was interesting collecting and composing details from flowing narratives into still images, I guess I hadn’t thought of writing as being a linear thing over time and had forgotten that drawings are a bunch of things in a 2d space.

Q3. Which parts were the collaboration were most enjoyable and which the most challenging?

The most enjoyable part was having fresh ideas to go off that I’d have never done alone. The trickiest was finding the best bits of overlap between our two practices, making an interesting image and also doing the writing justice.

Q4. How does the context of this publication impact on the work?

The fact that Patrick and myself are growing as creative working people makes the coming together of our work at this point in time just a bit more special, had this collaboration happened earlier or later I think the end result would have been quite different.

Q5. Would you take part in any future collaborations of this kind? Why?

Yep! It’s a good midway between my personal art practice and employable design practice, and I’m proud to have been involved in Patrick’s work which would’ve been great in my absence anyway.

You can purchase a copy of both books directly from our online shop, A Man Made Entirely of Bats and Panthers and the Museum of Fire. Or ask for them at your local bookshop. Trade inquiries, Dennis Jones & Associates.