Continuing our series of interviews with authors in our digital long story series, Michael McGirr Selects, this week we present Adelaide author, Rebekah Clarkson. Rebekah talks about her story ‘Dancing On Your Bones’ which is published as part of this digital series, about the lure of the thesaurus, what she’s reading and some tips about writing. You can preview and purchase Rebekah’s story below. Join Rebekah Clarkson in conversation with other writers and readers on Thursday, Oct 1 from 8pm AEST on the Spineless Wonders online bookclub. Details here.

Do you remember the name and personality of the first character you ever created?

Sadly, yes… a precocious turtle named Arthur. It was around the time I’d discovered Roget’s Thesaurus and I replaced every adjective, verb and adverb with the most convoluted synonyms I could find. I buried Arthur in the thesaurus.

What drove you to write the story which is in the Michael McGirr Selects series?

More than usual, there were multiple triggers and threads that drove me to write this story – they converged simultaneously. There was an article in our local paper a few years ago about a controversy in a nearby local government council over whether they would fly the Aboriginal flag alongside the Australian flag at their chambers. Some council members didn’t think it was appropriate. ‘Dancing on your Bones’ doesn’t use that incident specifically, but it was initially triggered by it. I wanted to sort of blow that up, but also couch it in a story about middle class aspiration and dissatisfaction. Using second person became a way to push the tensions in a range of issues that started to thread through the story. I really challenged myself with this story. Setting the story in Mount Barker, where I live, was another way of pushing my boundaries. I’m interested in writing about places that are both real and imagined, and in allowing what is spoken and unspoken in those places to find their way in. I also wanted to write a character who feels small and like an ‘outsider’, but who in fact has more power in the broader scheme of things than she realises. I wanted it to be intimate and awkward and satirical. As the various threads emerged, I had to find ways to weave them in and work out why they were there, or delete them. I wanted to touch some nerves and allow the story to be a little subversive. I think it’s an odd story in some ways…

How do you approach a new story? With a clear plan of where the narrative is going, or is it more of a ‘well, let’s see how this goes’ kind of approach?

There is always a trigger of some kind, usually more elusive than the one that initiated ‘Dancing on Your Bones’. The trigger might only be an ambience, or a single line of dialogue, an observed tiny paradox or irony or a dynamic in relationships, something that feels true that I can’t articulate. These triggers come all the time and I often write about them in journals, but to develop one into a story requires so much more discipline and perseverance than jotting in my journal; I have to turn up at the desk and stay there… The final story is often a long way from the starting trigger, but I can see it somewhere. I’m often surprised by where stories go and how they develop. Sometimes it takes me a few years before I really understand what is going on in a story. I prefer to discover the story as I’m writing. Whenever I’ve planned a story in the past, it tends to be contrived and have no real life, and by the time I’ve planned it, I’m bored and don’t want to write it so much.

Is there one particular author or book that you look to as a source of inspiration for your own writing? What are you reading now? Any recommendations?

I often have five or six books open to particular stories on my desk and I like to think I’m having some sort of  conversation with each of them as I’m writing, trying to aspire to something particular in each of them. It’s often a mix of old and new writers – Flannery O’Conner, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Raymond Carver, Eudora Welty, Alice Munro, Joyce Carol Oates, Alistair MacLeod, Edna O’Brien … too many to mention. I particularly love Jhumpa Lahiri’s stories for their compassion, insight and gentle humour. And I love Lorrie Moore’s stories for their empathy, satire and subversion. This is the fine line I hope to walk in my own writing – compassion and empathy with an element of subversion and a touch of satire. It’s easy to fall off onto either side of the line but these two writers, particularly when I think of the combination of their work, inspire me to stay on it.

conversation with each of them as I’m writing, trying to aspire to something particular in each of them. It’s often a mix of old and new writers – Flannery O’Conner, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Raymond Carver, Eudora Welty, Alice Munro, Joyce Carol Oates, Alistair MacLeod, Edna O’Brien … too many to mention. I particularly love Jhumpa Lahiri’s stories for their compassion, insight and gentle humour. And I love Lorrie Moore’s stories for their empathy, satire and subversion. This is the fine line I hope to walk in my own writing – compassion and empathy with an element of subversion and a touch of satire. It’s easy to fall off onto either side of the line but these two writers, particularly when I think of the combination of their work, inspire me to stay on it.

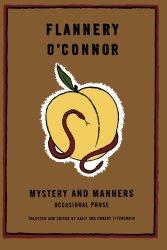

I think I’ve learnt more about writing from ‘The Art of Fiction’ interviews in the Paris Review, than from anywhere else. Flannery O’Conner’s stories have been a constant source of inspiration and also her essays – Mystery and Manners is never far from my desk. My favourite O’Conner quote is above my computer: ‘The fact is that the materials of the fiction writer are the humblest. Fiction is about everything human and we are made out of dust, and if you scorn getting yourself dusty, then you shouldn’t try and write fiction.’

I’ve just finished Elizabeth McCracken’s Thunderstruck. Her characterisation and dialogue (especially of children) is brilliant. Definitely recommend.

How does writing fit into your day-to-day life? Do you have any unusual writing habits? Any advice to share for those stuck in a writing slump?

I carve out periods where I can write in a sustained way, rather than in little grabs of time around other commitments, and as a result, I don’t write fiction every day. I suppose this goes against most advice about forming habits and being a ‘proper writer’ but I like to do lots of other things. I write in my head and think about stories most days though, and I don’t think this is wasted. I also write in journals a lot (which I don’t count as ‘writing’). If I am writing and I get stuck, going for a walk helps shake out an idea or an insight into a character. Maintaining solitude really helps too, when it’s possible, though this sounds precious I know and is mostly impossible. But if I can stay quiet and focussed in the world of the story (avoiding Facebook etc), it usually unfolds. Having a bath in the middle of a writing session is the ultimate. I also like to mull over a story just before sleeping to try and nudge it into a dream, which can be a great problem solver, even if it means you won’t sleep well. Mostly, I find reading is the best way out of a writing slump. Other writers are very inspiring. Another great way to stimulate writing, and I use it all the time when I’m teaching and mentoring, is to confine yourself somehow – a specific word count, a ‘non-negotiable’ prompt, ‘compulsory’ words or images: creative thinking is ultimately problem solving. The more confined you are, the more creative you become to get yourself out of the bind. I’ve learnt this particularly teaching children creative writing; they don’t necessarily want a blank page and the instruction to write ‘whatever you want’. But the more you restrict them, the more fired up they get.

Rebekah Clarkson’s short stories have been recognized in major awards and shortlists in Australia and overseas. They have appeared in publications including Best Australian Stories, Australian Book Review and Southerly and in Something Special, Something Rare: Outstanding short stories by Australian women (Black Ink, 2015). Rebekah lives in Adelaide.

Book available at Tomely