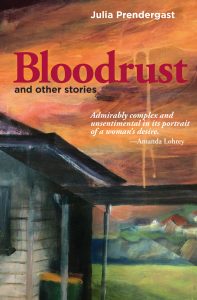

We are thrilled to be releasing Julia Prendergast’s debut short fiction collection, Bloodrust and other stories. In this post, Julia talks with Lucia Roohizadegan and Chloe Cran about the central themes of her collection, about writing literary fiction and offers advice to emerging authors.

Why do you write literary fiction?

Why do you write literary fiction?

Ah, deary me… This is such a superb question – the simple answer – I’ve always LOVED reading and writing.

And, perhaps, a not-so-simple answer…

In the height of the pandemic lockdown, I co-edited and contributed to a collection of prose and poetry: The Incompleteness of Human Experience. The collection was originally published online by TEXT Journal’: http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/ It was later published as a hard copy book (2020: Recent Work Press, co-ed Julia Prendergast, Eileen Herbert Goodall, Jen Webb).

In the afterword to this collection, I attempt to answer the question of what-I-write, how-I-write, why-I-write – why I’m obsessed with reading literary fiction – and why I love to engage with other writers as a Community-of-practice. An extract from the afterword:

In writing, I feel I’m often thrown into unpredictable territory. I go to places that, frankly, I’d prefer not to be. I feel that this is necessarily the case if I’m writing anything that is, well, worth writing. A writing colleague and friend wrote to me, at the very beginning of the crisis, explaining that she was ‘self-isolated, randomly enough, as the result of a fellowship in a writers’ house’. She added: ‘I’m writing lots of SEX, which is a little weird?’ My response (in full) read: ‘Not weird. Who chooses?’ Later, I wrote again. I said I’d just sent a new story out: ‘When I finished it, and read it a last time, I was like: Who wrote that?’ Is this how we feel when we write into the unknown, only to come to know it and eventually unknow it?

I am acutely interested in the relationship between what I see as the haunting incompleteness of human experience and short form writing. My writing always begins here: writing in a dream-like way from a state of conundrum and contradiction at the level of idea: something I am troubled by; something that presents a problem of logic or a riddle of emotion and logic; something I feel compelled to understand more fully. The act of producing narrative is a sensate response to conundrum and contradiction, a process of rumination and (perhaps) an antidote to ongoing rumination.

I defer, here, to Raymond Carver, “poster boy” for the dirty realist tradition. In an interview with Claude Grimal, titled ‘Stories Don’t Come Out of Thin Air’, Carver discusses the spark that ignites his writing. He says:

I use certain autobiographical elements [from my life… ] an image, a sentence I heard, something I saw that I did, and then I try to transform that into something else. Yes, there’s a little autobiography and, I hope, a lot of imagination. But there’s always a little element that throws off a spark […] Stories don’t come of thin air. There’s a spark. And that’s the kind of story that most interests me. (qtd. In Grimal 1996-6)

I resonate strongly with Carver’s “methodology” – writing from a spark. I always write from a riddle – conundrum and contradiction is the stimulus for all of my writing.

In the afterword to The Incompleteness Book, I also speak to the impact of word-work and story-work on my mind’s eye and my practice – as a writer, an editor, a writer-academic, and a person who has the great privilege and pleasure of teaching writing. This too speaks to my LOVE of literary fiction:

I think of the contributions [to the collection] that made me sob outright. I think of how I felt compelled to read them again, and again, trying to reconcile the emotional response with the content. In so doing, I remember a moment I’ve shared with many students, a real story about myself, as an undergraduate in a tutorial room on one of the upper floors of Monash Uni’s Menzies building – reading a poem I didn’t understand, sobbing outright and uncontrollably, excusing myself to collect myself. Later, I learned the poem was a lesbian love poem. Later, I reconciled my outburst with understanding – it was a day or so after Mothers’ day, my beautiful Mum had died, recently, and I had a new baby girl. I didn’t “understand” the poem; except of course I did, because I understood love between women. ‘Don’t worry if you don’t “get it”,’ I tell the students. ‘Ask yourself why the words make you feel the way they do. Get to the bottom of that…’

Asking ourselves how words make us feel – words as a vehicle for feeling-thinking – this is the motivational premise that underpins my obsession with literary fiction.

I was asked to contribute to The Brainwaves Video Anthology – on the the subject of ‘Why does fiction matter?’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGcbXocAOi0 In this contribution I talk about felt presences – Gordon Weaver asks: ‘in how small a space can [we] create the felt presences that animate successful stories?’ (1983: 228, my emphasis). Felt presences… in this concept I am reeling – the world becomes groundless – these words capture what literary fiction is and does, to my mind at least. Edith Wharton provides one of the best descriptions I have encountered, about the capacity of literary fiction to convey felt presences. Wharton says:

The impression produced by a landscape, a street or a house should always, to the novelist, be an event in the history of a soul, and the use of the “descriptive passage,” and its style, should be determined by the fact that it must depict only what the intelligence concerned would have noticed, and always in terms within the register of an intelligence. (Wharton 1997: 63, my emphasis)

How is it possible that story-work can enter our affect cycle as if it were lived experience? It’s magic, right? Word magic. This question is at the heart of what-I-write, how-I-write, why-I-write. I will spend my life thinking upon it – striving to write as a reader, read as a writer – and speculating upon this question in neuro/psychoanalytic terms, as a writer-researcher.

Do you have any other advice for writers in your genre on writing/ publishing/ marketing?

Write the stories you can’t-not-write.

Kafka says:

My feeling when I write something that is wrong might be depicted as follows […] A [person] stands before two holes in the ground […] waiting for something that can only rise up out of the hole to the right. Instead, apparitions rise, one after the other, from the left; they try to attract [the person’s] attention and finally even succeed in covering up the right hand hole. (qtd. in Corngold 1996: 84)

When I say write the stories you can’t-not-write, I mean let the story material take you where it will – “off-piste” as the case may be – then, as Carver suggests, try to make something from it. This is the nature of my methodology in story-work – it is an intuitive and messy way of working – the only way I “know how”.

Can you describe your writing process for short stories? Do you plan it thoroughly beforehand?

Nope. I am not a planner. I admire story planners but it’s simply not me. I write myself into a ridiculous mess and then do the work of unpacking concrete and specific detail, thinking carefully about the work of association and metaphor, the links between (seemingly) disparate elements of concrete and specific detail. If a story is worth working on, these details turn out to be intricately linked, and I work on the connections as the story-work progresses. To my mind, this is the pure joy of writing, finding the shape of the story. I NEVER begin with a shape or plan. I labour towards it.

There’s an emphasis on motherhood in the collection of Bloodrust stories. Did your own life experiences inform your short stories?

Yes.

I have six children aged: 29, 27, 25, 23, 21, 17. I learned I was pregnant with my first child, dear Albie, when I was 17. I didn’t want to terminate the pregnancy. As noted in the acknowledgements section of Bloodrust, I am the person I am because Albie, Amelia, Grace, Henry, Matilda and Heidi are my children. My stories are not about my life directly, but motherhood informs my humanity, at every turn, and I am grateful to my children, who are hilarious and loving, who “let me in” on their joys and heartbreaks, and who have chosen to be my friend.

Describe the themes and techniques used in Bloodrust.

I guess the overarching theme is “behind-closed-doors” stories. I’m interested in what we find if we scratch the surface of people’s humanity. Even those people who look like they have “tidy” lives on the outside are wrangling things, behind closed doors. More specifically, my stories focus on mothering, the conundrum of identity – identities plural (individual and collective, socially “defined” and self-determined, our “team of selves”) – mental health, suffering, love, desire, nature (human nature and our relationship with place), our exchanges with each other, especially in “threshold’ situations.

In terms of technique, as outlined above, my only technique is to write towards knowing – writing from the conundrum and contradiction, messily (wherever the writing takes me), listening to the vibrations of words and the narrative detail – searching for a form, a narrative architecture, that will do justice to the complexity of the inciting idea – and never with any expectation that there will be a “conclusion” or an “answer” or an “ending”. I don’t really like endings, it’s “a thing”, or perhaps I don’t believe in them – by which I mean to say that I think my stories are premised upon non-closure. A dear writing pal talked to me once about passing on the concern that drives the writing, to the reader. I LOVE this. It makes real sense to my inclinations as a writer and a reader. In writing I try to facilitate the reader’s engagement in an experiential world, rather than trying to provide any kind of resolution.

What role does love play in Bloodrust?

Ah, love is everything right? One of my children (Matilda) says: ‘You are a silver-lining person’. I hope it’s true. What’s my point? One of my readers commented that some of my stories are quite bleak. Others have suggested they are disturbing and hysterical, in equal measure. I think there is always a silver lining, by which I mean love, even in disturbing and bleak circumstances. I hope this carries in the stories.

Which is your favourite short story from the collection?

One of my favourites is ‘Like Clay’ – because of the way people have responded to it, and because of the way it brings urgency and longing, love and desire (familial and romantic), together. The central protagonist is Aaron, a teenager who delivers his baby sister on the kitchen floor – before his mother becomes afflicted with postpartum psychosis. Aaron is an amalgam of my Matthew, my boys – men I love who love and revere women, even in deep suffering.

Which story is the most relatable?

I think this is a question for readers. I’ve LOVED the random text messages people have sent me as they’ve been reading Bloodrust. Examples – ‘Contrapuntal’ [a story about the conundrum of mothering]: ‘This is my absolute fucking favourite so far. You beautiful, honest, clever woman’; ‘“The fuckwittery of mothering” – I want to get a tattoo of that line’; ‘This is the best thing you’ve ever written’ – ‘Today is Tomorrow’ [a story about forwards-backwards time, in pandemia]: ‘Connectivity issues’ Indeed’; ‘Exactly’ – ‘Two Day Room’: ‘This made me feel uncomfortable and obsessed all at once’ – ‘Like Clay – ‘I spat my drink when I read the bread and coke exchange’; ‘Love how the pre-hospital scene comes back in the sex scene; “we’re taking her in mate”’ – ‘The Wind in my Open Mouth’ – ‘What a gut punch’.

In many respects I write and want to crawl under a rock. But this is the pure joy, hearing that my stories have resonated with readers. Of a number of stories, in amalgam: ‘Your book, fucking love every word […] straw and Christmas and TIME, fuck me, forget about it’.

What inspired you to write Bloodrust?

I LOVE short-form stories.

Some years ago, my eldest son said: ‘I don’t know why you’re so obsessed with short stories. We just come to know the characters, and then they’re gone’. It’s so true. Like life, right? The haunting incompleteness of human experience – even when we feel we know people intimately and innately, there is this haunting incompleteness. Like no matter how much we love or know anyone we are, in some respects, orbiting the world “solo”. The brevity of short-form writing makes it an apt vessel for capturing the haunting incompleteness of human experience. My eldest son is (now) also obsessed with short stories. Glorious. There is a singular “rush” with short stories. They are addictive.

How does your experience of writing and publishing The Earth Does Not Get Fat differ from Bloodrust?

The writing process was similar – writing into the unknown… In the case of publishing, in both cases I feel inordinately grateful, that a publisher believes in the writing – is invested in it – is willing to back it. In the case of Bloodrust, I’m thrilled to be published by Spineless Wonders, because of their expansive vision for the form. Bloodrust includes traditional length short stories but also flash and micro stories. Spineless are leaders for their diverse and inclusive approach to short-form storytelling. I feel very lucky Spineless wanted to publish this collection of “mixed-mode” storytelling and privileged to have been bolstered by the team at Spineless.

Are you planning/ working on any future works? What can readers expect?

I never know what to expect so I think any answer I provide, here, will be dodgy. Having said that, ‘Like Clay’ is a story that won’t leave me alone. It remains unfinished in my mind. I began “writing back” it… I’m a slow writer and I have a day job (which I LOVE and I’m grateful for). What’s my point? ‘Get there faster,’ my eldest daughter, Amelia, says to me (often)…

I never know where the writing will take me. Let’s see.

About the Author

JULIA PRENDERGAST’S novel, The Earth Does Not Get Fat, was published in 2018 and longlisted for the Indie Book Awards for debut fiction. Her short stories have been recognised and published: Lightship Anthology International Short Story Competition (UK), Ink Tears International Short Story Competition, Glimmer Train International Short Story Competition (US), Séan Ó Faoláin International Short Story Competition, TEXT, Elizabeth Jolley Prize, Josephine Ulrick Prize.

JULIA PRENDERGAST’S novel, The Earth Does Not Get Fat, was published in 2018 and longlisted for the Indie Book Awards for debut fiction. Her short stories have been recognised and published: Lightship Anthology International Short Story Competition (UK), Ink Tears International Short Story Competition, Glimmer Train International Short Story Competition (US), Séan Ó Faoláin International Short Story Competition, TEXT, Elizabeth Jolley Prize, Josephine Ulrick Prize.

Photo credit: Rafael Fajer: New York Writers Workshop 2022

Purchase Bloodrust and other stories, here.

Works Cited

Grimal C, 1995-6, ‘Stories Don’t Come out of Thin Air’ in Prose as Architecture: Two interviews with Raymond Carver, Clockwatch Review Inc. trans Stull W L Interview translated from ‘L’Histoire ne descend pas des nuages’ Europe [Paris] 733 (May 1990): 72-79 https://titan.iwu.edu/~jplath/carver.html

Prendergast J, Strange S, Webb J (eds.) 2020, The Incompleteness Book, full-length edited collection, Canberra: Recent Work Press.

Prendergast J 2020, ‘Why Does Fiction Matter?’, A collection of over 1,500 videos with four million views in 234 countries, ‘Thinkers, Dreamers and Innovators; Some of the Brightest Minds in Education’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGcbXocAOi0

Wharton E 1997, The Writing of Fiction, Touchstone: Simon & Schuster.

Weaver G 1983, “Gordon Weaver.” Sudden Fiction: American Short Short Stories, edited by Robert Shapard and James Thomas, Gibbs Smith, pp. 228-9.