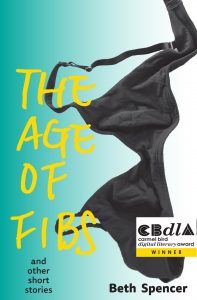

Beth Spencer, winner 2018 Carmel Bird Digital Literary Award, discusses the writing of The Age of Fibs with Bridgette Sulicich. Beth talks about her own reading and writing habits and about some of the inspirations behind this unique collection.

Bridgette: What is the most difficult part of the writing process for you?

Beth: The most difficult part for me is sitting with an idea that seemed great in my head and trying to capture it in words on a page, or facing what I wrote yesterday or last week or last year (some pieces have a very long incubation period). That uncomfortable gap between what you desire for a piece or a sentence and what it is, before the seemingly endless processes of revision and refinement. That daily facing up to a sense of failure and just sticking with it anyway. In the past few years I’ve been able to develop a swag of tricks and tools which have helped a lot, so I’m more able to move myself faster out of that paralysing shame and fear and into a more curious lighter attitude. And to be more at peace with the amount of time it takes, without that voice in my head judging me for not being able to get it or for being banal in the earlier drafts or taking so long. So I’m a little more relaxed about the process of evolving a piece of writing, and allowing it to be what it is in each moment. Allowing it to be terrible until it becomes not quite so terrible, and much more able to focus on enjoying the magic when it finally starts to click.

Beth: The most difficult part for me is sitting with an idea that seemed great in my head and trying to capture it in words on a page, or facing what I wrote yesterday or last week or last year (some pieces have a very long incubation period). That uncomfortable gap between what you desire for a piece or a sentence and what it is, before the seemingly endless processes of revision and refinement. That daily facing up to a sense of failure and just sticking with it anyway. In the past few years I’ve been able to develop a swag of tricks and tools which have helped a lot, so I’m more able to move myself faster out of that paralysing shame and fear and into a more curious lighter attitude. And to be more at peace with the amount of time it takes, without that voice in my head judging me for not being able to get it or for being banal in the earlier drafts or taking so long. So I’m a little more relaxed about the process of evolving a piece of writing, and allowing it to be what it is in each moment. Allowing it to be terrible until it becomes not quite so terrible, and much more able to focus on enjoying the magic when it finally starts to click.

Bridgette: Who are some of your favourite authors and what are you reading at the moment?

Beth: I have great gaps in my reading. We had few books when I was a child, especially new books, mainly just my mother’s 1920s and ‘30s Sunday School prize books, and I didn’t go to a school with a decent library until I was 15.

So in a sense my first narrative language was television, and I think this has had a big influence on my writing style. Television is full of story and emotion as it pulls you along, but its dominant structure is montage — juxtaposition of different texts and moving from one to the other and back again.

I love reading classical narrative novels and stories, and would have loved to be that kind of a writer. But in trying to explore and map my personal and cultural history and how I saw the world as a child of the ’60s and an adolescent in the suburban Australian ’70s, I seem to always gravitate towards a more fragmented, montaged, multi-voiced style.

And now, when we live in an age of super-accelerated fragmentation and an overload of different voices and styles in the way we interact with and create culture and meanings and stories, I have become even more distracted, multi-tasking and omnivorous in the way I read (or read and watch and read).

So it’s hard to single out some favourites. It depends on what I am seeking in that moment. I love the calming linear storytelling brilliance of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and I love the crazy disorder of George Saunder’s Lincoln in the Bardo. I love the diversity of what so many of my contemporaries are doing in Australian literature and poetry, and I probably love a different thing about each of them, without necessarily being able to point to any specific all time favourites.

And sadly I can no longer even point to my current beside-the-bed books as a biographical snapshot as I have piles of books beside, above, across from and on my bed, as well as a Kindle full of books. I’m not sure what kind of a reader I am any more. I am surrounded by things I wish I had the time and the focus to read. I wish I was a ‘better’ reader.

Bridgette: The title, ‘The Age of Fibs’, is an interesting play on words – referring as it does to an item of women’s apparel which played an important role in your growing up as well as to the act of telling lies or stretching the truth. For me, the ambiguity of the title remained even after reading the complete collection. Was this a deliberate choice to include both playful fiction in the collection as well as the more biographical stories?

Beth: Well I’m not sure I can make a distinction in my own work between memoir and fiction. Some pieces might lean a bit more one way than the other, but there is always a remembering process and an inventing process that is hard to untangle.

We alter a ‘past event’ every time we recall or retell it, as it mingles with whatever is going on for us in the present. There is no place (certainly not within language) where ‘the past’ exists as a pristine recoverable thing. The past is a complex of impressions, sensations, judgments, traces and assumptions. Every time we recall it for some purpose, or look at the evidence and traces it leaves it is to some extent a creative act, and a political act to the extent we ascribe meaning and story to it (and privilege a particular way of seeing or narrating it, particular kinds of voices or constructions). As a continual collective public process it is an important and constantly contested one, and I think it is as a personal process too.

And ‘The Age of Fibs’ seemed an apt title for the very serious and complex battle over the nature of ‘truth’ that we are currently experiencing.

Bridgette: Quite a few of the stories included in this collection seem very personal in content, for instance you have included in ‘The True Story of an Escape Artist’ a drawing that you made during a therapy session in 1993. How much of the stories are told from personal experience, and how much has been fictionalised? How difficult was it to write from such a personal perspective?

Beth: ‘The True Story of an Escape Artist’ was written for a book edited by Beth Yahp, called Family Pictures. I had terrible back ache from it for a long time afterwards.

I generally don’t have an inordinate amount of trouble with being revealing of my own stuff in my writing. In the moment of writing, it’s the needs of the piece that are paramount, and I try to deliberately not think about what it might be like to put this out in the world under my name and have others read it. And once written — once it’s gone through the long process of crafting and questioning and revision — it usually just feels like a story, not a confession or revelation. There is so much artifice involved, so much selection and editing and choosing. And then when it comes to putting it out there publicly, it is once again about what it needs as a story — its needs to be told or become part of the world, or become part of a particular conversation — and not about me. (Or not about the ‘me’ that I am having now written it, if that makes sense.)

But with the ‘True Story’ piece, I was using photographs of living people. (The brief was to write about any aspect of family using one or more photographs; most of the other writers were wise enough to write about people who were dead.) And I was writing it in the midst of a very fraught moment in my family’s history.

So: where does my story — and my right to tell my story — and their story begin and end? What happens when our stories overlap and in telling my story I am weaving a version of theirs and making in public in a way they will probably dispute but, as non-writers, can’t reciprocate with their own versions?

These were the questions that started a steady pain in my back, like being hit between the shoulder blades with a piece of four-by-two, and which took a long time to go away.

Fortunately, my family either didn’t read it, or were very forgiving. I hope they will forgive me for putting it out into the world again. (I love what one of my brothers said at the time when I was agonising about this: ‘They will be very very proud, and very very ashamed.’)

I do oscillate between feeling quite distant from it (it’s just a story now) and feeling full of apprehension about being so personal in public. In some ways I’ve moved on and changed, and then in a part of me it is all still very resonant and alive. I can perform a piece I wrote 30 years ago, as I did recently at La Mama, about something that happened in my childhood, and in that moment of performance I am right there again and, according to the feedback, so is the audience. Time is a strange thing when it comes to stories and emotions.

Bridgette: As a younger reader, there were some references throughout the collection that I didn’t immediately understand or recognise, such as the TV show Number 96, the Fibs bra, and the film Fatal Attraction. Do you think there is a risk of alienating your collection from some readers by including such specific and decade-oriented references?

Beth: Yes, there is. But this is a risk that is entailed in just about all history-telling, or telling stories about a particular time or culture. (Writing is a risky business.) I’d be interested in how you felt reading these pieces, not being familiar with the things referenced? Did you find it alienating?

Bridgette: With ‘Fatal Attraction in Newtown’, I personally found the style of the story attractive in its seamless shift between both reality and, for want of a better word, memory (memory of the film). Even though I haven’t seen the movie I was intrigued to read about the relationship between Dan and Alex, and the crazy things that seem to happen throughout their relationship, as well as the protagonists opinions and interactions with these.

I wasn’t alienated by the references that I didn’t understand, they made me want to seek those references out and see what I was missing out on. It inspired me to learn more about the culture of the 60s and 70s. I did feel that, at the time of reading it, I was missing a higher level of understanding, but I also felt firmly placed in the setting of the story.

Beth: Oh, that’s great to hear! I’m always amazed to hear back from young women who respond to the things I wrote about when I was younger. A few years ago I had some of my poetry translated into Chinese (published in a bilingual collection called The Party of Life) and it was such an extraordinary experience to have women from a different generation and different culture respond so deeply to my poems, even though they are littered with references to things like The Brady Bunch and Australian phrases that they had to ask about.

As for the story ‘Fatal Attraction in Newtown’, for me that was about critiquing a particular film that was culturally very significant and resonant, but it was also about creating a space of reference and history, about the matrix of ways these things interweave and the ways they contribute to us and we to them, and the ways we create and recreate ourselves using these things. So that, hopefully, each reader can extrapolate that relationship to their own situation, as well as maybe find the way it works for these particular characters interesting and evocative.

I particularly wanted to include this one as it was the 30th anniversary of Fatal Attraction last year, and it just seems so relevant again, with the #metoo movement.

It is a film in which there is so much violence against the Alex character (Glenn Close), and yet this was so normalised so as to be almost unnoticed as violence. It was portrayed as a film in which she is the dangerous one (the bunny burner). I wanted to write something that might explore and even change the way we look at that. So I’m very glad you engaged with it even though you haven’t seen or even heard of the film. I guess it just shows, unfortunately, how deeply this structure of blaming and silencing and violence towards women is still embedded in our culture.

Bridgette: I think this is a book that makes very relevant points that transverse time barriers about familial relationships and growing up. The psychology of the ways in which people form their own identity is a topic very prevalent today, and I think this book really speaks to that.

Beth: Thank you. That’s really heartening to hear.

Bridgette: Many of your pieces have been devised and performed for ABC Radio National, has this influenced your writing process and the ways in which you present your stories?

Beth: I was extremely fortunate to have a number of my pieces adapted and performed for radio, and to work with some terrific producers at ABC Radio National such as Claudia Taranto, Brent Clough and others.

I love radio because is a very intimate form, you are speaking right to each audience member in their home or car or while they are lying in bed. It’s a tactile form, relying on all the senses, and it works best when you break up a single voice with sounds or other texts or contrasting voices to create interest and a music of sorts. And I think this might be why it really suited me and my way of writing.

Radio also encourages you to write in a very easy colloquial style, a speaking voice, and for precision and clarity (people can’t go back and re-read that sentence if they don’t get it the first time). And it also has a momentum so that even when you don’t catch every second of what is being said or included (or have time to ponder the subtexts) you just keep moving with it and the whole knits up in your head in a way. You let it wash over you and the meaning comes to you in a full bodily way, not just through your thinking processes.

So this is something I aim for with my writing on the page, and why I also love performing it live or on radio. I love it when readers can just go with it, let it wash over them, and let the meanings accumulate and cross-fertilise. ‘Bodies speaking to other bodies’, as the Elizabeth Wright once said about the way texts work on us and we on them.

And of course, in the Age of Fibs, we need our public broadcaster more than ever. And the role of the ABC, like the role of ‘truth’ and who gets to tell what stories and where and when is deeply contested, as it is so important.

Bridgette: Thank you for taking the time to answer these questions.

— Beth Spencer and Bridgette Sulicich, September 2018

BETH SPENCER’s recent books are Vagabondage (UWAPublishing) and The Party of Life (Flying Islands). Awards include The Age Short Story Award, the Inaugural Dinny O’Hearn Fellowship and runner up for the Steele Rudd for How to Conceive of a Girl (Random House). She also writes essays and for radio. www.bethspencer.com.