This week, guest blogger, Karina Brabham dives into the work of two short fiction greats, Britain’s late Angela Carter and Australia’s Margo Lanagan, to find out how they each take something old and turn it into something shiny and new.

Writers are recyclers at heart. Not necessarily in an environmental sense, but rather that we recycle stories. We tell the same plot lines over and over again. If we look back to the earliest examples of stories – myths, legends, folk and fairy tales – they resemble a lot of what we tell today. They have birthed the formulas of plot the reader knows too well – and yet despite this predictability, they continue to be told.

There are many examples of explicit retellings of older stories. Disney’s adaptations of fairy tales are an obvious case in point. More literary examples also present themselves such as, in the short story context, Angela Carter’s rewritings of fairy tales in The Bloody Chamber and other stories. Our familiarity with the fairy tales is what enables Carter to subvert them for her own feminist agenda.

In ‘The Bloody Chamber’, for example, Carter makes some significant deviations from the traditional plot of the Bluebeard myth. Instead of the brothers of the Bluebeard character’s wife riding to her rescue, it is her mother in Carter’s version. The mother, as Carter created her, is a startling figure of female empowerment – she has “outfaced a junkful of Chinese pirates, nursed a village through a visitation of the plague, shot a man-eating tiger with her own hand”. She is indomitable yet still maternal. In contrast to Charles Perrault’s original Bluebeard, Carter does not allow women to be exclusively branded as victims; they can be heroines too.

Yet the danger here is to only value Carter’s collection of rewritten stories on their political level. Although her manipulation of known plots facilitated her message, it is limiting to solely name this as the reason for the piece’s success. Setting, language, tone and a whole host of other features make up a story – it is how the writer handles these that is the key to making something fresh from the recycled tales we know too well. From the beginning of ‘The Bloody Chamber’ a dark and ominous tone haunts the pages, created through foreshadowing, imagery and symbolism. Carter captures the reader as the tense atmosphere of the story builds to its climax.

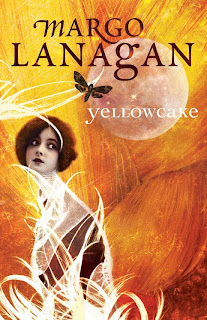

Margo Lanagan, in her new collection of short stories Yellowcake, recycles old tales in a less overtly political but no less effective manner. Two of her short stories, ‘The Golden Shroud’ and ‘Night of the Firstlings’, are both recognisable as new versions of old tales.

‘The Golden Shroud’ is a retelling of the Rapunzel story told from the Prince’s perspective. From his point of view the story clearly shines as a tale of young love fraught with the threat of loss. The Prince’s youthful voice provides a vitality which engages the reader anew with this old tale. It is told in Lanagan’s distinct style that highlights an emotional intensity of the character’s experience. In her version the reader is immediately thrust into the Prince’s despair at finding his beloved gone from her tower and her abundance of hair lying on the ground. The strong images she creates within the fabric of the story add a visual beauty that catches the reader’s imagination. For example:

“I lay in the slippery whorl of her hair, the spread sun on the ground, trailing and looping out into the green. I smelt, I felt, the grass through the perfumed strands pillowing my cheek. What had the old bitch done: had she killed her? Had she worse? Had she found worse than this tower and this tether of hair?”

According to the acknowledgements in Yellowcake, Lanagan’s ‘Night of the Firstlings’ was inspired by the Paul Kelly song ‘Passed Over’. This song is, in turn, is a musical retelling of the Biblical story of the Jewish people’s escape from slavery in Egypt. It focuses on the final plague when the angel of death passed over, taking the eldest son from every family – except those with lamb’s blood painted on the doorway.

Lanagan again grounds the story in the immediacy of one character’s experience. This point of view adds a vividness to the tale which a reading of the source story in Exodus does not offer. The terror of the moment as death passes over is given a horrifying reality to the reader. Lanagan builds up the tone through each word and each image, chosen specifically for this purpose. With the narrator, the reader hears it:

“The noise blotted out every other noise, louder than the wildest wind, and composed, in its beatings, of beating voices, crowds shrieking terrified or angry or in horrible pain I could not tell, and the groans of people trampled under the crowd’s feet, and the screams of mourners and the wails of the bereaved, all the bereaved there have ever been, all there will be, torrents of them, blast after blast.”

By taking something old and recycling it, something new can be made. In the hands of superb writers, like Carter and Lanagan, these retellings are fresh and vibrant despite having begun centuries ago. In fact, the history behind it means it can be built on and taken in entirely new directions. We see that clearly in Carter’s feminist rewritings of fairy tales. We see that through the lens of what has already been said, what is said differently becomes so much more significant. Yet above all, as writers, we learn that it is not a plot that makes a story – although a good plot always helps – it is often rather how we tell the story which determines how great it will be.

Margo Lanagan blogs here at Among Amid While