1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

I admire Cate Kennedy immensely — Dark Roots feels like perfection to me. I (like so many people) was also hugely impressed with Nam Le’s The Boat, and other Australian collections I’ve loved include Josephine Rowe’s stories-in-miniature, When a Moth Becomes a Boat; the early collections of Gail Jones (Fetish Lives and The House of Breathing) and Joan London (Sister Ships), and recent collections by Susan Midalia (The History of the Beanbag) and Richard Rossiter (Arrhythmia). And I’ve just finished Janette Turner Hospital’s Forecast: Turbulence — wonderful!

2. What is the most memorable short story you have read? And why does it stand out for you?

Only one? Oh, that’s tough! I might have to go with an Australian classic: Marjorie Bernard’s ‘The Persimmon Tree’, for its hauntingly beautiful final image of the naked woman glimpsed through the window — the simultaneous elusiveness and knowledge it seems to convey. Or (see my cunning plan to slip in another favourite?) there’s Julio Cortázar’s ‘Axolotl’; from the very first paragraph, when narrator comes to the stunning realisation that he has become the creature he has been studying, this taps into visceral fears of being buried alive — an existential horror story!

3. What do you like about the short story form?

I love the tension between compression and expansion. You work with fragments, with glimpses and moments, and if you get it right, something whole will emerge from them — something that feels true — not the truth but a truth. I think of Walter Benjamin’s observation that ‘knowledge comes only in flashes’. This feels like the short story’s territory: that moment of seeing, of revelation. And I love the idea that we enter a story’s moment (whether that is the space of an hour or a day, or years such as in Annie Proulx’s long/short story ‘Brokeback Mountain’) and then leave it — and its world and its people continue in both directions, just as life does; the story has just cracked a window open for us to see a moment of change.

4. How would you describe your own writing?

I think other people are far better at doing that. I can tell you some of the reasons I write, though. I write to work out what people think, what I think; to imagine why people do the things they do, to imagine what I would do; to try on other shoes, other skins; to puzzle over why things are the way they are; sometimes just to glory in the way they are. I don’t expect to find, or offer, answers or wisdom but hope for an insight or two along the way.

5. Which of your stories are you most fond of right at this moment and why?

I think perhaps it’s the first story in Inherited, ‘Dance Memory’. The young widow, Jo, her little son Nicky, the ageing wheelchair-bound dancer Mignette, the family of ducks—they’re still very much alive for me. This story is one of several I’ve written about the ‘things’ of a life, the possessions we accumulate, our ‘stuff’, and, as the most recent of them, maybe it comes closest to saying what I’m trying to say.

6. Where do the ideas for your stories come from? (Take us through an example)

Anywhere. Everywhere. ‘Gratitude’, for example, came from my puzzling over the proliferation of roadside crosses marking the site of fatal accidents — wondering whether they give comfort to those left behind, whether they claim something sacred about the site of death. And then I happened to notice a succession of photos in newspapers — grief-stricken parents, husbands, wives, all holding up to the camera photographs of their lost ones. These faces seemed to bear the same expression of despair and outrage. And so ‘Gratitude’ came from an observation, a few photographs in a newspaper — an attempt to make sense of what I was seeing, and to think about grief and what it is that helps people to carry on after tragedy, or prevents them from doing that.

7. What is your writing process – from idea to publication? (Do you go it alone or are others involved?)

It’s a long, long process usually. I often think about an idea for a long time (sometimes years), just jotting down notes, before I actually begin writing, and then the drafting and redrafting can take many months. I have a few trusted writing friends with whom I exchange work for feedback, and I couldn’t do without their honesty and thoughtful responses.

8. Do you feel the short story form is valued in Australia? What makes you say this?

I think it is cherished by many people. Unfortunately, this affection doesn’t always extend to a wide readership (or translate into sales). But things could change. Short fiction is perfect when you have limited reading time, and offers the immense satisfaction that comes from being able to read something in its entirety in one sitting. And there have been quite a few collections published recently. Maybe we’re on the cusp of a renaissance of the genre? I would love to think so.

9. How do you feel about your work being published in non-print forms such as digital and audio?

I’ve worked in publishing (as a book editor) for more than twenty years, and I watch with great interest today’s changing publishing landscape. I confess to having an abiding fondness for ink and paper, but I feel privileged to have my work published in any medium. It’s great that readers can access stories in whatever way they prefer to read or listen.

10. What advice would you like to offer Spineless Wonders?

Well, my advice to writers is always to read — but I don’t think I need to tell you that!

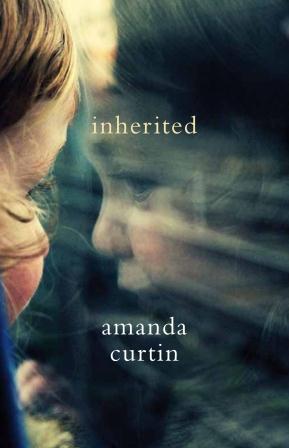

Amanda Curtin is a novelist and an award-winning writer of short fiction. Her collection, Inherited (2011), and her first novel, The Sinkings (2008), both published by UWA Publishing, have met with critical acclaim. Amanda lives with her husband and her cat in an old house in an old suburb of Perth, and is currently completing her second novel.

For more on Inherited see: http://uwap.uwa.edu.au/books-and-authors/book/inherited/

Watch the book trailer for Inherited at: