1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

1. Who are the short fiction authors you admire (Australian or otherwise, alive or dead)?

There are so many! But some who spring to mind include Anne Enright, Wells Tower, Peter Carey, Alice Munro, Raymond Carver, Borges, Kafka.

2.What is the most memorable short story you have read? And why does it stand out for you?

If pressed to name a single one, I’d have to go for Kafka’s ‘The Metamorphosis’. It is a nightmare put on paper, distilling the horror hidden in a certain kind of ordinary existence. The image of a man suddenly and inexplicably transformed into a grotesque insect could be read as an allegory for many things: mental illness, neurotic self-rejection, the fate of the sensitive man in a bourgeois, materialistic society. What makes it great literature is that almost everyone who reads it shudders with an obscure sense of recognition. Somehow it is a universal nightmare.

3. What do you like about the short story form?

Ben Okri once described a novel as like a river, a short story as like a glass of water. That seems utterly apt to me. It captures the short story’s clarity, its self-containment, its capacity to be taken at a gulp – and a certain salutary asceticism about it. I suspect that ascetic quality is why the short story languishes in today’s culture, along with the poem. Short stories do not satisfy in the complete, explicit way of novels or movies. They sit subtly on the mind after one has finished them, pervading the intellect and the emotions, suggesting associations and meanings the way a fine wine suggests cinnamon or vanilla (to perform a Jesus-like trick on Ben Okri’s metaphor). To enjoy them requires the capacity for subtlety, and indeed they teach subtlety. Unfortunately, we do not live in subtle times.

4. How would you describe your own writing?

I suppose I veer towards the melancholic, the elegiac, sometimes the blackly comedic. Writing is no fun if you’re not expressing forbidden thoughts and feelings. In my case, it seems to be the suspicion that things are more awful than we like to admit. The freedom of writing is honesty, unglossed by our usual defensive manoeuvres. Yet I think there’s an aesthetic sensibility to my writing that brings a redemptive touch, even if the story is black. I treat my characters with empathy and sensitivity, even while I torture them!

5. Which of your stories are you most fond of right at this moment and why?

Right this very moment I harbour an affection for the odd man out in of my collection: ‘Comrade Vasilii Goes to War’. It’s the shortest story and unusual in being set on the border of two fictional eastern European countries when all the others are set in (more or less) modern Australia. Somehow I feel a great warmth for the bumbling, self-effacing Vasilii. Perhaps, when I think about it, it’s that he actually is a hero of sorts, in spite of his conviction that he is the worst soldier there ever was.

6. Where do the ideas for your stories come from? (Take us through an example)

Autobiography is always a great starting point, though the stories seldom remain there. Autobiography is like an armature you can build on. It can give you the confidence and the structure to start crafting something. Then slowly the thing starts to want to take its own shape, and eventually the real events are so deeply buried only I, the author, can still make out the rough bones of them underneath. Sometimes the story starts with someone else’s life. ‘The Thief’ – about a jazz guitarist in the late sixties – was based on my old jazz guitar teacher who died sadly of a stroke a number of years ago. He told me once about how he had heard ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ for the first time on the radio while driving in his kombi van, and how much it had moved him. I imagined the circumstances of that moment and it became the seed for the whole story.

7. What is your writing process – from idea to publication? (Do you go it alone or are others involved?)

It begins in anguish and procrastination. I always have many ideas, none of which seem quite good enough. I start many, many more stories than I finish, a bad habit, because in truth I believe that the failure of a story should not be an end point. It should be the beginning of the next incarnation, born from the ashes of the last through a process of understanding what went wrong. Many of my final stories are like that – refined from countless cycles of death and rebirth like the Buddha! Still, I suffer from the delusion that perhaps this time, writing won’t be such hard work.

As for the involvement of others, yes I absolutely believe in that and rely on it. I have a hardy band of reliable critics whose feedback I always solicit before sending my work anywhere. A good writing group is gold.

8. Do you feel the short story form is valued in Australia? What makes you say this?

Valued by whom? It is valued highly by a certain subculture of literary types, but the value ascribed to it by the broader culture can be assessed easily enough from the financial rewards of writing them. Money is our system of agreed value, and while one can make a living from such activities as spamming ads for penis enhancement pills, bashing people weaker than oneself outside of nightclubs, and short selling collapsing stock markets, even a rare talent like Cate Kennedy can’t make half of a decent living out of writing short stories. It’s quite remarkable that we do it at all given how painful and difficult it can be, the number of brusque rejections we face, and how pitiful the pay cheques are (if we get one at all). And most of the money comes indirectly from government grants; it’s not even a reflection of true market value. Fortunately those who do value it, value it deeply, and it’s for those people we keep going.

9. How do you feel about your work being published in non-print forms such as digital and audio?

I think I’m not alone among writers in my sentimental attachment to good old paper. And maybe there’s good reason for that. Talking about value, to put words on paper (trees after all) is to enshrine them in a valuable medium, to bestow the dignity of a certain permanence. Whereas we know from all the worthless blogs, all the proliferating online verbiage, just how cheap a byte is these days. It’s hard to know the value of what you do once your product is virtual, once it vanishes it into the great, undifferentiated digital sea. That said, the economics of the e-book are becoming increasingly compelling and if e-books and e-readers help to create a new generation of literary readers, I’m all for them. As for audio books, I adore the idea of being someone’s bedtime story.

10. What advice would you like to offer Spineless Wonders?

No advice, just thanks for bearing the standard for Aussie short story writers.

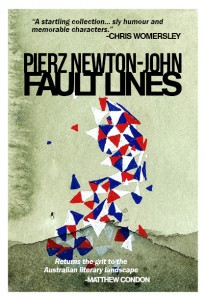

Pierz Newton-John lives in Melbourne. In addition to being a writer, he is a guitarist, web developer, former psychotherapist and father. His stories have appeared extensively in Australian literary journals and anthologies including Meanjin, Overland, New Australian Stories, Kill Your Darlings and The Sleepers Almanac. He won the Alan Marshall Award in 2008 for ‘This Old Man’. His collection, Fault Lines, published by Spineless Wonders will be launched in Melbourne on March 15th at the Hill of Content Bookshop.