I was at an artist’s retreat in the US. Flicking through a book in the library one evening, I came across a reproduction of Arshile Gorky’s painting The Artist and His Mother. I knew – know – very little about painting but something about this just skewered me. I read the caption which told me that Gorky was a survivor of the Armenian Genocide. The what? I wondered … I googled the Armenian Genocide and spent hours reading in a state of horror and disbelief. How could this have happened? How could I not have known that this happened? There’s a quote that came up often. Hitler, right before the invasion of Poland in 1939: “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

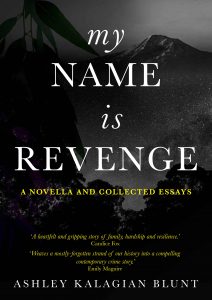

Read Emily Maguire’s launch of Ashley Kalagian Blunt’s My Name Is Revenge and Collected Essays which Maguire describes as ‘a gut punch of a book, a necessary and urgent shout back to the silence’.

The Sydney launch of My Name Is Revenge was held at the Acres Eatery, Camperdown on 10 April, 2019. This is the full text of the speech given at the event by acclaimed author, Emily Maguire.

The Sydney launch of My Name Is Revenge was held at the Acres Eatery, Camperdown on 10 April, 2019. This is the full text of the speech given at the event by acclaimed author, Emily Maguire.

It’s a hot December morning in 1980. Vrezh, a PhD student living with his family in Lane Cove wakes to the news that the Turkish consul-general to Sydney and his bodyguard have been murdered. This has happened just across the harbour in Vaucluse.

As he pores over reports of the assassination, Vrezh imagines the scene, wondering if his older brother Armen was the shooter. It’s a thought that gives him a sense of ‘curious pride…and envy.’ He imagines the scene, putting himself in the picture – imagines himself ‘climbing off the Honda’s pillion seat, walking toward the car, drawing the gun, aiming through the windscreen….’

It’s chilling. This is a highly educated young man living with his loving family on Sydney’s leafy north shore who feels empowered by the assassination of a Turkish diplomat. What the hell is his problem, you might well ask. And, we’ll come to that, but to get there, I want to take you on a bit of tangent and talk about a moment from another excellent book I read recently.

It’s a memoir called Educated and it’s by Tara Westover, a woman who was raised and home-schooled by religious extremist, militant survivalists in rural Idaho. She eventually makes it to university against all odds and there’s this moment in her first weeks there, where she comes across the word holocaust in a caption under a picture. She asks, with genuine innocence, ‘what is this word? I don’t know it’. Her classmates are horrified. Her lecturer, taking her question as an off-colour attempt at humour says ‘Thanks for that’ and moves on.

There is no way for anyone in that room to process her question except as a sick joke, no way for the reader to take it except as a further proof of how completely her parents shut her off from the world.

When I read this scene, I was struck with a memory from a decade ago. I was at an artist’s retreat in the US. Flicking through a book in the library one evening, I came across a reproduction of Arshile Gorky’s painting The Artist and His Mother. I knew – know – very little about painting but something about this just skewered me. I read the caption which told me that Gorky was a survivor of the Armenian Genocide.

The what? I wondered. We were called in to dinner and I mentioned the painting, asked the gathered dozen or so artists what they knew about Gorky. One of the painters there knew quite a bit about his work and the conversation flowed into a discussion of abstract expressionism and its relationship to surrealism. I wondered aloud about the Armenian genocide; what had happened to Gorky and the mother who stared out from that painting so accusingly. There was a bit of muttering. Nobody seemed to know specifics. Someone unhelpfully pointed out that surviving tragedy has an effect on one’s art. The conversation moved to the art that came out of the holocaust and then on to something else again.

After dinner I googled the Armenian Genocide and spent hours reading in a state of horror and disbelief. How could this have happened? How could I not have known that this happened? There’s a quote that came up often. Hitler, right before the invasion of Poland in 1939: “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

He said that twenty-four years after the genocide. He could say the same today. Unlike Westover who was alone in her ignorance of the Holocaust, any first year uni student who came across the caption next to Gorky’s painting, as I did, and asked, what is this Armenian genocide? would be unlikely to be met with howls of disbelief.

Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation – attempted annihilation – of the Armenians?

Vrezh’s family speaks of it. His grandfather is, like Gorky, a survivor and his trauma and grief pulse through the blood of his entire family. Vrezh has known his whole life why his family is so broken and lost that he cannot complete a simple family tree project at school. He knows why his grandfather screams in the night.

Vrezh’s family speaks of it. His grandfather is, like Gorky, a survivor and his trauma and grief pulse through the blood of his entire family. Vrezh has known his whole life why his family is so broken and lost that he cannot complete a simple family tree project at school. He knows why his grandfather screams in the night.

But outside of the family, it is like it never happened. At school Vrezh’s attempts to speak about the history of his people are silenced. He must write about Simpson and his donkey not an Armenian hero. He must commemorate Anzac Day and not mention what happened the day before – April 24 1915 – the beginning of a campaign of terror and violence which would leave more than one million Armenians dead and many more traumatised and displaced.

All of this has brought Vrezh to that initially inexplicable point: excited by the assassination, day-dreaming of being involved. Then he does more than daydream: inserting himself into a plot to commit further vengeful violence.

As he gets in deeper and deeper we’re forced to grapple with some big questions: what happens to a child who grows up being told the experience of his family is not real? What comes from celebrating certain acts of state sanctioned violence and silencing or denying accounts of others? What might someone do when they feel justice is impossible, revenge or submission their only options?

The compassionate but unflinching examination of these questions makes My Name is Revenge a gut punch of a book, a necessary and urgent shout back to the silence.

I want to be able to say: Read this book because it is important; it will teach you something about the past and make you think differently about now. To say that, and know it will be enough. For some of you that will be enough. Excellent. But as someone whose last book was about a woman grieving her murdered sister, I know from experience that no matter how worthy the topic it’s hard to get people excited about reading something that sounds, in summary, really fricking depressing.

So, I want to assure you that despite the necessarily confronting and upsetting subject matter, My Name is Revenge is not a grim read! It is an absolutely cracking, tension-filled crime story that will grab you in the first pages and hold you tight and breathless until the end. And then, after it’s over, the characters will stick around, haunting you in the best possible way. You’ll walk around wondering about them, why they went down the paths they did, what might have made a difference and when and how?

That’s where the second part of the book comes in. The three short essays are as cleanly and elegantly written as the novella. They, too, will grab you quickly and hold you tight throughout, although you may – as I did – need to stop a few times to process the reality of what you’re reading or to gaze awhile at the photos of people and places that have survived all this, that are still here to tell the stories the rest of the world would rather forget.

One of those people is Ashley Kalagian Blunt. I’m grateful to her for writing My Name is Revenge and delighted to help launch it into the world tonight. Thank you, Ashley.

Launch photos courtesy of Francesca Guidici.

EMILY MAGUIRE is the author of five novels and two non-fiction books. Her latest novel, An Isolated Incident was shortlisted for the Stella Prize, the ABIA Literary Fiction Book of the Year and the Miles Franklin Literary Award. Emily’s articles and essays on sex, feminism, culture and literature have been published widely including in The Sydney Morning Herald, The Australian, The Observer and The Age. Emily works as a teacher and as a mentor to young and emerging writers.