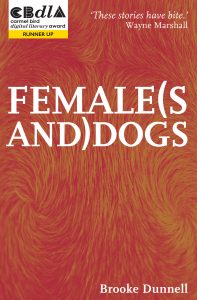

In this post, Bridgette Sulicich and Dahlia Mikha interview Brooke Dunnell about her award-winning short story collection, Female(s and) Dogs. Brooke talks about the importance of creating complex characters, about the origins of some of the stories in her collection. She answers the key questions of why dogs and why female dogs and shares her own experiences of growing up with canines.

How important was it to represent a collection of stories focussed on women and featuring the entire gamut of personalities and traits (rejecting the idea of simply ‘good’ or ‘bad’ characters)?

As a writer and reader I’m always interested in characters who are complex in their traits and motivations. While these stories were all themed around the treatment and experiences of women and girls, I didn’t want the female characters in the stories to be universally ‘good’ or always victims of their circumstances. Similarly, despite what’s going on with power and gender in the stories, I didn’t want all the male characters to be simply ‘bad’. Even with characters who do seem to have a lot of negative traits, I’m hoping that readers will understand that things are going on socially, emotionally, psychologically, etc. that make them behave in the way they do in the moments captured in the stories.

Did you settle on females(s and) dogs being the binding characteristic of each story early on, and where did you draw inspiration from?

I wrote a couple of the stories (‘Honey’ and ‘Baby’) inspired by other things, then realised they both featured dogs and their vulnerable female owners. I also had the novella ‘The Spaniel’, which had this great Shakespeare quote: ‘I am your spaniel, the more you beat me I will fawn on you’. From there the theme suggested itself to me, along with the idea that there was more to explore about female experiences alongside this dog/’female dog’ motif. I mused for a while on the other different approaches I could take and the final three stories ‘The Mistress’, ‘Bella’ and ‘Killer’ came out of that.

I wrote a couple of the stories (‘Honey’ and ‘Baby’) inspired by other things, then realised they both featured dogs and their vulnerable female owners. I also had the novella ‘The Spaniel’, which had this great Shakespeare quote: ‘I am your spaniel, the more you beat me I will fawn on you’. From there the theme suggested itself to me, along with the idea that there was more to explore about female experiences alongside this dog/’female dog’ motif. I mused for a while on the other different approaches I could take and the final three stories ‘The Mistress’, ‘Bella’ and ‘Killer’ came out of that.

You write from a range of views through the collection, differing genders and differing ages. How did you find alternating between these voices through the writing stage?

I wrote each of the stories independently, basically finishing one before I began another, so I didn’t have to worry too much about taking on different voices and points of view one day to the next. In general, I wanted to have these different protagonists – males and females of different ages and different demographics – to make each of the stories feel individual and self-contained, despite being linked to the others thematically. It was important to show that the mistreatment of women, or the association of women with female dogs, can pop up anywhere, whether intentional or not.

Of all of your characters, is there one that you particularly identify with or love?

Casper in ‘Honey’ is quite sweet – he’s a kind, well-meaning widower who just wants to keep to himself. He’s lovable to me because he wants to protect his neighbour, even though he doesn’t really know what’s going on with her, and deep down he doesn’t want to know.

I also feel a lot of compassion for Teagan in ‘Killer’ because of how trapped she feels and the loathsomeness of some of the small experiences she has. She tries to do a good thing in the face of fear and possible violence, but she just makes things worse.

The animals in your stories seem to act as crutches of emotional support to your characters, did you have dogs growing up and have they played a large part in your life?

We had a dog when I was younger but I didn’t interact with him too much because I was quite little and he was an outside dog. I’m definitely of the mindset that ‘all dogs are good boys – except the ones who are good girls’. My husband and I were both keen to have dogs, and a few years into our relationship we got a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel named Jed who is now six and a half. Some time later we got a second Cav called Lenny – not because Jed was desperate for companionship (he wasn’t, and he still isn’t!), but because we wanted a second pup. Our lives basically revolve around them. The first story that really sparked the collection, ‘Honey’, was written after I’d been thinking about what I’d do if anyone really threatened my dogs – how far would I go to protect them? That gave me the idea of Michelle wanting to get rid of her Lab to protect the dog from this malevolent force.

Many writers struggle to create dialogue that flows naturally, yet you seem to write dialogue effortlessly. Where does your skill emanate from, do you think, and what advice would you give to writers wishing to develop their skills in this area?

Thank you, that’s a great compliment! I love dialogue and how it can be used to communicate information as well as show character, convey realism… it does so many things. I feel like when I’m writing I ‘hear’ the dialogue and basically just transcribe it. I want it to feel realistic and have those qualities that real dialogue has, like slang and incomplete grammar, without being confusing.

I think my advice would be to really listen to the way that people around you talk. The turns of phrase and vocabulary that people use in real life are fantastic and you can learn so much by paying attention to it. I think it’s good if writers also critically assess their dialogue and consider whether anyone they know really talks like that.

As an author, how do you balance dialogue with action? Did one of them help you develop characters or progress the story better than the other?

I definitely feel more comfortable and original when it comes to dialogue. I often pepper my first drafts with a lot of inconsequential actions, like characters making faces or turning away or picking stuff up and putting it down. In second drafts I go through and take a lot of it out because it’s not doing anything. It might be reflecting reality, but apart from that there’s nothing useful happening, and you can’t waste words in a short story. I usually don’t need to remove nearly as much dialogue because it feels like it’s doing the work that I want it to – demonstrating character as well as moving the story forward.

How do you manage to create such life-like characters? Is there a process you follow or does it come naturally to you?

Thank you again! I’d have to say that it isn’t anything I’m super conscious of doing. I guess if I looked into it there’d be some subconscious work taking place in order to balance realistic and life-like character traits with the requirements of the story. While half of the stories in this collection were created as a result of considering the theme I’d come up with, usually my stories start with characters and then the plot and themes come out of that. I think this approach can help a character to seem life-like – they aren’t just a tool to help the plot.

Brooke Dunnell is a Perth writer whose short fiction has been published in Best Australian Stories, Meanjin, Westerly and other journals and anthologies. Her work has been recognised in a range of competitions including the Neilma Sidney Short Story Prize 2017 and the Bridport Short Story Prize 2019.

Brooke Dunnell is a Perth writer whose short fiction has been published in Best Australian Stories, Meanjin, Westerly and other journals and anthologies. Her work has been recognised in a range of competitions including the Neilma Sidney Short Story Prize 2017 and the Bridport Short Story Prize 2019.