We are delighted to bring you the text in full of Cassandra Atherton’s speech at the launch of Richard Holt’s debut collection, What You Might Find at St Kilda Readings earlier this year. Richard’s reply to this wonderful launch speech was to perform a few songs based on stories from the collection on his newly-invented guitarpwriter.

We are delighted to bring you the text in full of Cassandra Atherton’s speech at the launch of Richard Holt’s debut collection, What You Might Find at St Kilda Readings earlier this year. Richard’s reply to this wonderful launch speech was to perform a few songs based on stories from the collection on his newly-invented guitarpwriter.

Hello and thank you for coming to the launch of Richard Holt’s book of microfiction, What You Might Find. My name is Cassandra Atherton and I’m honoured to be launching such a brilliant, memorable book that is quite unlike any you’ve ever read before.

What You Might Find is Richard Holt’s debut collection of microfiction –he is a writer who is known for his proficiency in this short form (as well as his use of visual art and narrative), so this collection is much anticipated. At the outset I want to say that we generally use the term microlit as an umbrella term for very short fiction and prose poetry. But other popular terms are microfiction, flash fiction, sudden prose and even postcard fiction. Microlit in Australia is flourishing and it is slowly getting the attention it deserves from publishers. Now, many Australian writers include prose poetry and flash fiction in their collections and microlit in anthologies continues to grow, legitimising it as a popular form in Australia.

What is exciting about Holt’s What You Might Find is that is a collection entirely devoted to microlit. This does not mean that all of the pieces are of the same length – indeed they range across many different lengths and styles and Holt pushes the boundaries of the form in new and exciting ways. By doing this, he responds to the challenges of postmodern society with the rich fragmentation and multivalency in his microfiction. This means that all of his stories – whether they are set somewhere else in time, or somewhere recognisable –provide fascinating commentary on the more philosophical considerations of what it means to live today.

Holt does this by expertly crafting the form in a way that asks more of the reader than other writers of the short form do. Using metaphor and metonymy – he asks the reader to fill in the gaps and it’s a heady experience, as a reader, to feel that you are entering the narrative and making a difference to its interpretation. This experience is also enhanced by Holt’s use of pared back language which is occasionally juxtaposed with a moment of lush description or technicolour moments of realisation. This happens in stories like “Rollin’”, “The Game” and “The Perfect House” where the last line ushers in a moment of realisation that things are not as they appear. And it’s the way this book turns on things that are secret or concealed that make it rich and textured.

One of my favourite stories is “The Swimmer”. I’d like to read it – that’s the luxury of microfiction, you don’t have to excerpt it. Notice the way the protagonist changes from understanding and seeing himself in one way, only to have that moment turned on its head. It’s about shifting perspectives and slow realisation:

The Swimmer

One morning, while running, Ollie Perovic thought he spotted a swimmer momentarily within the featurelessness of the new day’s grey, but he couldn’t be sure. There was no colour, no contrast. No light or dark. No horizon. Later he imagined perhaps he heard a distant voice calling but, as it was early spring, plenty of boisterous groups were using the foreshore—boot camp warriors and football clubs—so he thought nothing of it. No one passed as he trudged up the hill to the beacon and over to the footbridge.

Only later that day, as he headed back to the office from Soup King, did Ollie recall the two possibilities, the swimmer and the voice, each as uncertain as each other. The coincidence of these memories brought about a kind of dread, which stuck with him all afternoon. He was unable to concentrate on the Pathways Report and found himself checking online news sites every few minutes. Though the media reported no one missing, his brooding uncertainty persisted.

A week later, as he shuffled along the sand of Eastern Beach in the thickness of another fog he heard a call from the direction of the waves. He pulled off his running shoes and t-shirt and leapt into the water. He was a better swimmer than runner and had put three hundred metres between himself and the shore before he realised the icy conditions were getting the better of him. His limbs began to cramp. An all-over shiver ran through him. Looking to the shore he could just make out a figure on the beachside path, jogging in a heavy, plodding gait that seemed familiar. Ollie Perovic called, across the waves with all that was left of his flagging strength.

Holt’s microfictions are Carver-esque – not only in their minimalism, but in their dirty realism.

And so the readers’ expectations –along with the protagonist’s –are subverted. It’s brilliantly clever, like the unreliable narrator in the best literature, the reader can’t trust what they are reading until they get to the end and make sense of it. Then, like all good microfiction, you want to go back and read it again.

Holt’s characters deserve attention. Many of them are wonderfully curmudgeonly – more than one eats dinner alone after reading a note on the fridge from his partner like the narrator in “Post” and Lester in “Fading Towards Infinity”.

These characters mull over concepts of infinity and have often expansive imaginations, which are in stark contrast to their monotonous lives. In this way, Holt’s microfictions are Carver-esque – not only in their minimalism, but in their dirty realism. If Carver writes about working class people in the heartland of America who are often down and out on their luck, Holt writes about the lost, lonely and left behind in Australia.

If Carver explores the underbelly of the American Dream, then Holt shows us what happens to the Australian Dream when the dream of owning your own house has become an unattainable dream for many people. And this often leads some characters into trying to find ways around this. Some are dreamers, others gamble to try to get ahead by doing something other than working hard and playing by the rules – with rising house prices and the difficulty of permanent well-paying jobs it critiques contemporary Australian society for the younger generation. The best example of this is the story “Gambling” which is reminiscent of the Kenny Rogers song, “The Gambler”, only this gambler has a sting in the tail. There’s also the roll of dice on whether a man stays with or leaves his wife in “Rollin’” even a dark lie at the heart of a key sporting event in “The Line”.

One of the things I love the most about Holt’s work is his use of black humour and it is distinctively Australian in its expression of the uncanny. Let me read you the brilliant opening of the piece, “Severance”. I found myself laughing at the horror of it.

from Severance

from Severance

The downtown train did not, exactly, cut Lester Anderson’s head off. Even if it had, Lester would have loathed the inelegance of his demise so described. He’d have resolved that split phrasal verb—relocated its dangling ‘off’—before you could say boo. ‘Cut off Lester’s head’… pedantry perhaps, but Lester had always been a stickler. It had become a problem for him—made things worse, that need not have been made worse.

The point being, Lester’s decapitation was not strictly a cutting, but rather a linear obliteration, courtesy of the crushing of a two-inch-wide strip that had once been his neck. The result was the inevitable and complete separation of the parts either side. Save for Lester’s missing neck—a surprisingly complex few inches—the dismantling was clean.

Skull and jaw unharmed, brain intact, Lester—his head to be precise—had rolled between the roaring clatter of the bogeys and come to rest, comfortably enough, one cheek against a concrete sleeper.

There’s something about this story that reminds me of the Hitchcock movie, Strangers on a Train in its exploration of the idea of coincidence and it also reminds me of the film Stranger Than Fiction in its quirky exploration of things that seem too unreal to be fictionalised. In short, I guess I’m saying it’s strange in the best way that strange is memorable and quirky.

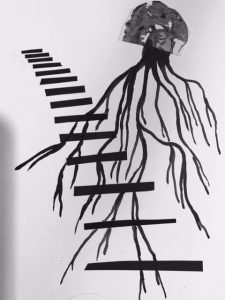

As it turns out, in Holt’s story, everyone on the train that is responsible for decapitating Martin is connected to him – either overtly or more implicitly. It’s accompanied by a brilliant image by Bettina Kaiser of a head on tracks with nerves sprouting in a web of directions emphasising both the gaps and connections on the tracks.

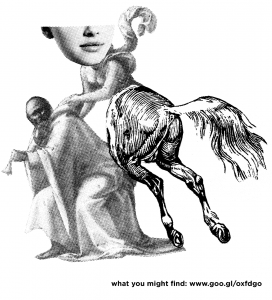

Finally, I’d like to turn my attention to two of the longer short stories in this collection. The first is The Temptation of Ludovico Carracci and uses real Renaissance painters to conjure a story of being double crossed in the art world that has lasting repercussions. Holt has discussed that this story was inspired by a trip to an exhibition and by reality television…I love that combination and again it speaks to the way Holt is keen to contemporize the  lessons from history in order to critique contemporary society. This story charts rivalries between women in a closed environment in Bologna. In the final moments, as the story crosses back into the present day, we realise that history has been painted over but is now accessible in peeling back the paint on the canvas to read the secret message/apology beneath. As with all excellent microfiction, I can’t read the end out or it will ruin the story – but it’s brilliant and accompanied by another of Kaiser’s unique but distinctively humorous images that includes the rear end of a horse.

lessons from history in order to critique contemporary society. This story charts rivalries between women in a closed environment in Bologna. In the final moments, as the story crosses back into the present day, we realise that history has been painted over but is now accessible in peeling back the paint on the canvas to read the secret message/apology beneath. As with all excellent microfiction, I can’t read the end out or it will ruin the story – but it’s brilliant and accompanied by another of Kaiser’s unique but distinctively humorous images that includes the rear end of a horse.

The final story I want to discuss is “The Locked Half-Blood”, a term for a knot that is used in fishing and becomes an extended metaphor or conceit in this work. The story begins quite lyrically with a rumination that pitches somewhere “between hope and despair” for the protagonist. Importantly, it is only through confronting his past that Frank can move on and perhaps even form a lasting relationship with a woman. I’m going to just read the beginning to give you a taste:

Sometimes the only clue that the tide has turned is the sound of the slap of water on weathered timbers. Long after dark there’s a pause, then the flow returns, but in the opposite direction. With a bit of luck the fish go on the bite.

With a bit of luck… Sometimes you wait what seems forever but the change never comes.

So what you might find in this book is much more than you expected. Holt’s brilliantly minimalist microfiction bursts from its frames, reaching outwards to encompass so much more than the sum of its parts. Holt is a master of the microlit genre and I encourage you to buy a copy of the book and see the craft involved in writing this form; it’s breathtaking.

So what you might find in this book is much more than you expected. Holt’s brilliantly minimalist microfiction bursts from its frames, reaching outwards to encompass so much more than the sum of its parts. Holt is a master of the microlit genre and I encourage you to buy a copy of the book and see the craft involved in writing this form; it’s breathtaking.

I now declare this book – Richard Holt’s What You Might Find, officially launched.

Cassandra Atherton is judge of TheNWF/ joanne burns Microlit Award and series editor of the annual Spineless Wonders’ microlit anthology. An award-winning writer and critic, Cassandra is an expert on prose poetry. She is an associate professor at Deakin University in Literary Studies and Creative Writing and was also recently a Harvard Visiting Scholar in English. Her most recent books of prose poetry are Trace (Finlay Lloyd, 2015) and Exhumed (Grand Parade, 2015).

Photo credit: Melissa O’Donovan